Australia’s Future Presence in the Solomon Islands

13 June 2022 | Fraser Wipp

Executive summary

The ‘Pacific Step-Up’ strategy was first outlined in Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy whitepaper, which aimed to “pursue common interests and respond to the region’s fundamental challenges” [1]. Australia’s Step-Up was designed as a long-term initiative to strengthen regional engagement through security co-operation, development aid, trade, investment, and cultural diplomacy. This paper advocates for a significant revision of the strategy to improve Australia’s relationship with the Solomon Islands.

The recent Solomon Islands’ announcement of a bilateral security treaty with China has shown that more needs to be done to improve Australia’s diplomatic and strategic relationship with the island country, as the realities of heightened regional security competition have become increasingly apparent. This new strategic environment should also be taken into consideration when deciding how best to engage in more productive dialogues with regional partners, ensuring Australia’s national interest is protected while also promoting regional stability.

The security capabilities of the Solomon Islands have faced renewed pressure as recently as November 2021, when the Australian government provided a joint Australian Defence Force (ADF)-Australian Federal Police (AFP) deployment to help end rioting in the state capital of Honiara. Since then, a minimised presence has been maintained in the Solomon Islands in accordance with bilateral security commitments. Future defence cooperation strategies should also seek to provide integrated health assistance, climate change and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) policies. This will be necessary in the immediate future to strengthen Australia’s regional security commitments, while promoting stability and prosperity for the mutual benefit of all Pacific nations.

Policy recommendations

To strengthen its relationship with the Solomon Islands, Australia should:

- Review peacekeeping capabilities to prepare for possible future interventions. The limitations unearthed from reports made during and after the RAMSI mission should be taken into consideration when assessing Australia’s post-2017 bilateral security commitments. Future budgetary and ADF personnel increases should prioritise training exercises and civil-military cooperation within the Solomon Islands, as well as language training.

- Co-operate with allies and regional partners to address root causes of civil strife and unrest in the Solomon Islands, including the uneven distribution of economic gains in communities outside Honiara. Diversifying the economy away from its traditional reliance on logging exports can emphasise Australia’s status as a preferred trade and investment partner by providing a clear alternative to ‘debt trap diplomacy’.

- Hold more regional security dialogues in the immediate future, prioritising climate change mitigation and preparedness strategies and demonstrating leadership within the ‘Pacific Family’. If Australia is not seen to be taking climate change seriously through these dialogues and policy initiatives, then it risks undermining its position as a genuine diplomatic partner of the Pacific Islands.

- Station more diplomats and region-specific policy experts in the Solomon Islands. The new 2022-23 budget allocation for the revamped High Commission building provides a further opportunity to expand Australia’s diplomatic outreach beyond Honiara through education, language training and other relationship-building initiatives. Increased diplomatic engagement in these areas can improve state capacity alongside existing technological and infrastructural investments.

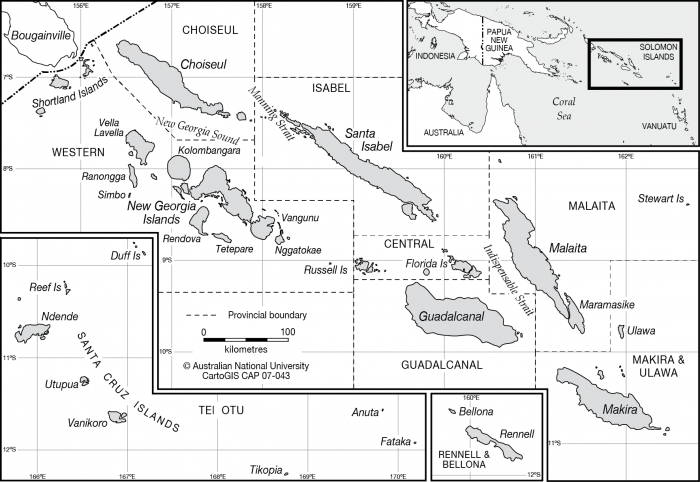

Figure 1: Solomon Islands regional boundaries. Source: Australian National University

Introduction

There are currently sixty AFP officers working with the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force, these officers were first deployed in November 2021 alongside the ADF to quell rioting [2]. Whilst the officers are playing a crucial role, focus has shifted towards facilitating the growth of the Solomon Islands’ independent policing and security arrangements. Future policing and security co-operation should aim to prevent the need for further significant deployments, and thus avoiding the need for another intervention akin to Australia’s 2003-2017 RAMSI peacekeeping mission. Australia should instead prioritise expanding its approach towards state capacity building, encompassing economic development as well as multilateral regional security dialogues and initiatives.

Australia is the primary developmental assistance partner of the Solomon Islands with an established history of peacekeeping commitments highlighted by the RAMSI mission [3]. A recent call for troops to be deployed during riots and the announcement of a security treaty between China and the Solomon Islands has cast aspersions on the long-term effectiveness of Australia’s engagement strategy. Future policy revisions have an imperative to go much deeper, beyond merely increasing existing aid commitments or fast-tracking infrastructure projects.

Australia must also prioritise rebuilding and strengthening diplomatic ties across the Solomon Islands, so that the underlying causes of past and present disturbances to regional security can be more adequately addressed. Existing disaster relief programs, peacekeeping protocols and trade policies should be supplemented with a revised approach to collective security, which broadens and deepens Australia’s engagement with its Pacific Island partners.

Australian intervention in the Solomon Islands – Past and present

In a 2003 article titled ‘Responding to State Failure – The Case of Australia and Solomon Islands’, Dr. Elsina Wainwright described the Solomon Islands as “a failing state” [4]. The pivotal piece played a crucial role in the Howard Government’s decision to accept a request for intervention from then-Prime Minister Allan Kemakeza. This prompted the launch of a long-term peacekeeping operation within the region, known as the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).

Australia had previously maintained a hands-off approach to curbing regional instability, avoiding measures which could impede upon sovereignty or be regarded as neo-colonial in nature. Prime Minister Bartholomew Ulufa’alu’s previous request for intervention in 2000 had likewise been denied [5], in part due to Australia at the time, being “heavily committed in East Timor”[6]. The 2003 RAMSI Mission would finally conclude on June 30th, 2017 [7].

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) have also played a significant role in shaping and mediating regional security policies. Importantly, during a meeting in Kiribati in October 2000, PIF leaders drafted the Biketawa Declaration. This declaration was designed as a key mechanism to pre-emptively address and “enable a regional response to crises” after coups had occurred in Fiji and the Solomon Islands [8]. This was also consulted when drawing up the 2017 bilateral security treaty between Australia and the Solomon Islands, which allowed for “Australian police, defence and associated civilian personnel to deploy rapidly to Solomon Islands if the need arises and where both countries consent”[9]. These measures provide substantive collective and bilateral security frameworks. However, Australia can do more to address and help resolve underlying issues which have led to these flashpoints of civil unrest.

When reviewing the limitations of RAMSI, it has been noted that the mission “focused too much on implementing established programs and projects, but not on working with the church and other influential civil society elements” [10]. Another drawback cited was the difficulty in constructing a clear exit strategy for RAMSI personnel. As a consequence, capacity-building suffered, as “Dependencies were built up, especially among some Treasury, Finance, and Health officials who were placed directly into Solomon Island ministries” [11]. To provide a renewed focus on future capacity building initiatives, more Australian diplomats with regional expertise should be stationed in the Solomons. Prioritising broader civic engagement in rural communities outside Honiara could help make lasting improvements to civil society beyond immediate, short-term security objectives. For this to be successful, language training should be earmarked for future Defence Cooperation Program (DCP) budgets.

One immediate security objective during the early stages of RAMSI involved the disarmament of local militia groups, notably including the Malaita Eagle Force and the Isatabu Freedom Movement [12]. As a result, firearms are now only permitted to be held by police on the Islands. However, the parallel assistance provided during the recent riots from Australia and New Zealand as well as China, could potentially complicate future security and policing arrangements. To mitigate some of the recently cited risks, especially of undeclared weapons being shipped to the Islands, future Ministerial dialogues should prioritise greater oversight and ensuring that firearms remain strictly controlled by the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force [13].

Figure 2: Humanitarian Aid deployment during ‘Operation Lilia’, 14 February, 2022. Source: Defence Images Australia

Climate change, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief

Pacific Island nations are geographically vulnerable to climate change pressures, including rising sea levels, desalination, and extreme weather events. In 2020, Cyclone Harold struck the area, which is the most recent tragic example of this vulnerability. The PIF have often highlighted these regional challenges, with its 2018 ‘Boe Declaration on Regional Security’ stating that “climate change remains the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Pacific” [14]. The PIF have stated a strong commitment to implementing the policy objectives of the Paris Climate Accords.

Pacific Island leaders have repeatedly called for Australia to take stronger action regarding its climate policy. Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama recently called for Australia and other developed nations to “come with commitments for serious cuts in emissions by 2030 –– 50% or more” before the COP26 summit [15]. While Australia has made significant investments in climate resilient infrastructure and renewable energy, more can be done to embed climate policy objectives within regional security frameworks to help alleviate these concerns.

Another limitation of Australia’s ‘Pacific Step-Up’ has been that it is often viewed as being unilateral in nature. Dr. Wesley Morgan, a research fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute, has argued that Australia has thus far paid “insufficient attention to Pacific-led processes of regional cooperation” [16]. “Pacific regionalism has developed its own guiding ideas, shared norms, and even regional sources of international law – all of which are important to Pacific Island countries”, Morgan argues, therefore the largely unilateral approach to the ‘Step-Up’ could stand to benefit from increasing consultation efforts, “[developing] regional initiatives together with Island states” [18]. Working closely with the PIF to finalise the 2050 Blue Pacific strategy, which was previously expected to be delivered in 2021, could help Australia to begin remedying this perception [19]. This would help to solidify its reputation as a regional stakeholder with a distinct role separate from its traditional security approach of ‘strategic denial’.

There has been increased recent discussion of the prospect of Australia hosting the 2024 COP29 Climate Summit. If the summit is to take place in Australia, a Pacific Islands partnership should be prioritised, consulting with each of the 14 Pacific Island leaders beforehand [20]. The 2022 federal budget has pledged to double the funding of the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific to $3 billion [21], which would see renewed focus on “climate-resilient infrastructure”[22], however it is Australia’s diplomatic engagement regarding climate security which also needs to be expanded. By concretely pledging to the Pacific Islands Forum to not only meet its target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, but to significantly reduce emissions by 2030, Australia can further demonstrate that it shares and prioritises the genuine concerns of its Pacific partners.

A recent Royal Australian Air Force deployment has assisted ground efforts by the Australian Medical Assistance Team (AUSMAT) to provide essential COVID-19 relief packages and personnel [23]. This provides a foundational example for future cooperative health and food assistance efforts. Specific provinces targeted due to “experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases” could potentially see other emergency aid distributed under similar protocols [24]. In the event of a future humanitarian crisis, emergency relief efforts like AUSMAT should be expanded into a multilateral partnership with neighbouring countries. This could include requesting the United States’ assistance in delivering and improving vital healthcare services, and developing a more regular rotation of clinicians stationed in the Solomons. AUSMAT can also provide a more in-depth skills transfer in provincial public health sectors outside Honiara.

The United States intends to re-open its embassy in the Solomon Islands, which can provide a de-politicised civic engagement initiative with communities across the islands [25]. This undertaking strengthens public health services on a much more permanent, mutually beneficial basis, and does so outside of the typical framework of self-interested great power competition.

Maritime security co-operation

Maritime security provides another opportunity for closer regional security cooperation with the United States, which involves improving intelligence sharing to better protect and preserve Pacific Islands fisheries. The US has recently adopted a strategy of “deploying Coast Guard ships to the region under ‘Shiprider’ agreements, which allow the local authorities to board American vessels and enforce local and international fishing laws” [26]. Operation SOLANIA has also sought to complement the pre-existing “aerial surveillance component of the Australian Government’s Maritime Security Program, which provides contracted aircraft for the FFA to use up to 365 days a year across 15 Pacific Island nations” [27]. This operation involved “a Royal Australian Air Force C-27J Spartan aircraft [providing] aerial surveillance”[28] and helped support the coordinated maritime surveillance and patrol operations of the Pacific Island Forum Fisheries Agency [29].

These existing approaches to maritime surveillance should be expanded on a formalised, multilateral basis. This would seek to improve the future coordination of similar operations, while enhancing the abilities of regional partners to track, prosecute and prevent theft and overfishing. A recent appendix to Australia’s 2022-23 Portfolio Budget Statements regarding the Defence Cooperation Program has also set a future precedent for this, stating that “The key area of growth in 2022-23 is in multilateral activities under the Pacific Patrol Boat Program / Pacific Maritime Security Program” [30].

Economic development and soft power

Uneven development gains regarding resource distribution and critical infrastructure have been identified as some of the root causes of inter-ethnic conflict on the Islands, notably between Guadalcanal and Malaita. The Solomon Islands’ economy has also been heavily reliant upon logging exports, which are vulnerable to natural disasters and price shocks. Providing minimal local returns in rural areas, they have also been marked by contentious land rights arrangements. Although existing infrastructure projects like the Tina River hydropower facility [31] are essential in providing renewable energy to the Islands, more can be done outside Honiara to diversify the economy and avoid the further entrenchment of ‘clientelism’[32].

Australia has the capacity to provide leadership through soft power as the preferred development partner for the Solomons. This includes technological developments, including expanded access to broadcasting and telecommunications networks. It can also include, as Dr. Anthony Bergin has suggested, a renewed focus on “[establishing] an emerging business leaders program of mentorship and training programs for Pacific entrepreneurs” [33], achieved through a public-private partnership with leading business schools in Australia and the United States.

Diplomatic outreach

In order to step up its diplomatic efforts, Australia’s approach to regional security dialogues and co-operation should be reconsidered. Professor Joanne Wallis and Dr. Anna Powles, two specialists on the Pacific region, have argued that Australia can do much more to include Pacific nations directly in collective security dialogues, instead of sidelining them. Wallis and Powles contend that this should include more multilateral security dialogues, whether they are formal or informal, including Track 1.5 security dialogues [34]. These dialogues, involving “Australian, New Zealand and Pacific Islands officials and non-governmental experts”, can be held on a regular basis to provide further clarification and consensus on collective security priorities [35]. The 2020 “Australia–New Zealand–United States Pacific Security Cooperation Dialogue” [36], specifically sought to include representatives of the Pacific Islands on its panel and reportedly resulted in positive discussions. Holding more of these dialogues in the future, whether on an annual or biannual basis, should serve to improve mutual trust and help provide greater assurances regarding future security co-operation.

Figure 3: Solomon Islands with location map. Source: Australian National University

Responding to the Memorandum of Understanding

The recent announcement of a bilateral security treaty between China and the Solomon Islands has been heavily criticised by Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Micronesia among others [37]. The agreement enables “a considerable People’s Liberation Army (PLA) military presence” on the Islands for security cooperation and police training [38]. It would also “permit the PLA Navy routine ship visits and logistical replenishments” [39]. Critics of have voiced concerns not only about the initial memorandum, but its potential expansion into a Pacific-wide security pact.

The treaty itself does not include provisions for China to construct a naval base. However, a similar narrative unfolded during the early development stages of the Djibouti naval base. Throughout 2017, “it was reported by international and even some Chinese media as China’s first overseas naval base, although Beijing officially described it as a logistics facility” [40]. The signing of this treaty and its associated discourse are a stark reminder of the increased strategic tensions within the region, and the strongest indicator thus far that Australia must do more to step up its diplomatic engagement with the Solomon Islands and its Pacific neighbours.

The Solomon Islands’ political landscape and democratic institutional legitimacy is currently also facing significant stresses due to these developments. There has been a dramatic escalation in recent years, with the “rhetoric, posturing and symbols of geopolitical competition [having] been appropriated by Solomon Islander actors on both sides of longstanding domestic political tensions” [41]. Political leaders like Malaitan Premier Daniel Suidani have been emboldened in the context of increased cooperation between Beijing and Honiara, beginning with his vehement opposition to Prime Minister Sogavare’s 2019 decision to reverse official recognition of Taiwan [42]. Suidani has pledged to reject any political and business influence from China within Malaita, and supported the no-confidence motion filed by opposition leader Matthew Wale that called for a referendum regarding Malaitan independence. These actions have only solidified the perception that he and his supporters are in conflict with a “central government out of touch with the province and a perennial lack of economic development for Malaita” [43].

Taiwan and the United States have since pledged their renewed support for developmental assistance to the province, with the US allocating a “US$25 million aid package directly to the Malaitan government, fifty times what the province would normally get in a year from donors” [44]. The broader geopolitical context of increased security competition has had a destabilising effects on the Solomons’ domestic political situation and should also be considered when addressing the causes of inter-island tensions. However, rather than framing the Solomon Islands as a state which is simply acted upon by others, it must be considered as a sovereign entity just as capable of hedging, bargaining, and balancing as its largest trade and development partners.

Australia can build a stronger, closer relationship with the Solomon Islands and the Pacific region more broadly, by emphasising Australia’s unique capabilities as a preferred partner and providing “a robust approach to security-related needs in the region” [45]. This will require further civic engagement with local communities and their respective leaders, rather than liaising near-exclusively with Honiara. It also requires emphasising non-traditional forms of security, prioritising climate security threats in regional dialogues, and promoting infrastructure projects and disaster relief programs. Australia’s immediate strategy for diplomatic engagement should ultimately be expanded while retaining its ongoing bilateral agreement with the Solomon Islands’ security apparatus.

Conclusion

Australia should continue to update its regional security policy agenda to meet the new challenges of the Pacific when addressing any of its concerns regarding the Solomon Islands. By doing so, the underlying causes of past disturbances can be better addressed and hopefully resolved. Australia can also focus on revising its diplomatic engagement strategy with the Solomons, prioritising rural civic engagement, climate change mitigation, maritime security cooperation, and an expanded Defence Cooperation Program. Despite the uncertainties brought about by geo-strategic competition between the United States and China, Australia remains uniquely capable of stabilising the Pacific security environment by learning from past interventions and revising its foreign policy to better suit the needs of its Pacific partners.

About the auth or

or

Fraser Wipp is a Research Analyst Intern in the Semester 1 2022 UWA DSI Internship Program. He is currently studying a Master of International Relations at the University of Western Australia. LinkedIn

Notes

[1] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. (Canberra, ACT: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017): 101. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-foreign-policy-white-paper.pdf. Online Accessed: May 8th, 2022.

[2] Australian Federal Police. “AFP Commissioner and eight members return home from Solomon Islands” Australian Federal Police, January 31st, 2022. https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/afp-commissioner-and-eight-members-return-home-solomon-islands. Online Accessed: May 8th, 2022.

[3] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “Solomon Islands country brief” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (Canberra, ACT: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2022). https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/solomon-islands/solomon-islands-country-brief. Online Accessed: May 8th, 2022.

[4] Elsina Wainwright. “Responding to State Failure-the Case of Australia and Solomon Islands.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 57, no. 3 (2003): 487. https://doi.org/10.1080/1035771032000142608.

[5] Wainwright, “Responding to State Failure – the Case of Australia and Solomon Islands.”, 491.

[6] Wainwright, “Responding to State Failure – the Case of Australia and Solomon Islands.”, 491.

[7] Clive Moore. “The End of Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (2003-17).” The Journal of Pacific History 53, no. 2 (2018): 164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2018.1472521.

[8] Moore, “The End of Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (2003-17)”, 164.

[9] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “Bilateral Security Treaty.” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (Canberra, ACT: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2018). https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/solomon-islands/Pages/Bilateral-security-treaty Online Accessed: May 9th, 2022.

[10] John IV Gordon and Jason H. Campbell, Organising for Peace Operations: Lessons Learned from Bougainville, East Timor, and the Solomon Islands. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016: 85. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1556-1.html.

[11] Gordon and Campbell, Organising for Peace Operations: Lessons Learned from Bougainville, East Timor, and the Solomon Islands, 85.

[12] Jeni Whalan, How Peace Operations Work: Power, Legitimacy, and Effectiveness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013: 161. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199672189.001.0001.

[13] Stephen Dziedzic and Evan Wasuka. “Calls for clarity over China’s shipment of ‘replica guns’ to Solomon Islands after Honiara riots” ABC News, March 17th, 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-17/replica-guns-shipment-solomon-islands-china/100916026

[14] Pacific Islands Forum. “Boe Declaration on Regional Security.” Pacific Islands Forum. September 5th, 2018. https://www.forumsec.org/2018/09/05/boe-declaration-on-regional-security/

[15] Hon. Josaia V. Bainimarama. “Come with commitments to COP26: Forum Chair statement on IPCC report” Pacific Islands Forum, August 12th, 2021. https://www.forumsec.org/2021/08/20/come-with-commitments-to-cop26-forum-chair-statement-on-ipcc-report/. Online Accessed: May 9th, 2022.

[16] Wesley Morgan. “Large Ocean States: Pacific Regionalism and Climate Security in a New Era of Geostrategic Competition.” East Asia (Piscataway, N.J.) 39, no. 1 (2021): 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-021-09377-8.

[17] Morgan. “Large Ocean States: Pacific Regionalism and Climate Security in a New Era of Geostrategic Competition.” East Asia (Piscataway, N.J.) (2021): 46.

[18] Morgan. “Large Ocean States: Pacific Regionalism and Climate Security in a New Era of Geostrategic Competition.” East Asia (Piscataway, N.J.) (2021): 57.

[19] Pacific Islands Forum. The 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent. Pacific Islands Forum. https://www.forumsec.org/2050strategy/ Online Accessed: 17th April 2022.

[20] Geoff Chambers. “Carbon cuts: ALP climate policy targets big emitters”. The Australian. December 4th, 2021. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/labor-reveals-2030-emissions-target-of-43pc/news-story/d4b381f2c4001842ec1069d2514794c8

[21] Tom Burton. “New $65m Honiara embassy as Pacific aid hits a record.” Australian Financial Review. March 29th, 2022. https://www.afr.com/technology/new-65m-honiara-embassy-as-pacific-aid-hits-a-record-20220328-p5a8jy

[22] Burton, “New $65m Honiara embassy as Pacific aid hits a record.”, Australian Financial Review. 2022.

[23] Hon. Marise Payne, Peter Dutton, and Zed Seselja. “Deployment of Royal Australian Air Force to support Solomon Islands COVID-19 response”. Minister for Foreign Affairs. February 14th, 2022. https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-release/deployment-royal-australian-air-force-support-solomon-islands-covid-19-response

[24] Payne, Dutton, and Seselja. “Deployment of Royal Australian Air Force to support Solomon Islands COVID-19 response”. Minister for Foreign Affairs. 2022

[25] Edward Wong and Damien Cave. “Blinken Says U.S. Has a ‘Long-Term Future’ in the Pacific Islands”. New York Times. February 12th, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/12/us/politics/blinken-fiji-pacific-islands.html

[26] Wong and Cave, “Blinken Says U.S. Has a ‘Long-Term Future’ in the Pacific Islands”. New York Times. 2022.

[27] Department of Defence. “ADF supports effort against illegal fishing in the Pacific.” Defence News. November 6th, 2020. https://news.defence.gov.au/media/media-releases/adf-supports-effort-against-illegal-fishing-pacific Online Accessed: April 11th, 2022

[28] Department of Defence, “ADF supports effort against illegal fishing in the Pacific.” Defence News. 2020.

[29] Department of Defence, “ADF supports effort against illegal fishing in the Pacific.” Defence News. 2020.

[30] Department of Defence, Portfolio Budget Statements 2022-23. (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, 2022): 99. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/information-disclosures/budgets/budget-2022-23 Online Accessed: 18th April 2022.

[31] AIFFP. “Tina River Hydropower Transmission System”. Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, 2022. https://www.aiffp.gov.au/investments/investment-list/tina-river-hydropower-transmission-system. Online Accessed: May 8th, 2022.

[32] Terence Wood. “The Clientelism Trap in Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, and Its Impact on Aid Policy.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 5, no. 3 (2018): 481–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.239.

[33] Anthony Bergin. “This is our backyard, not China’s”. ASPI Opinion. 2021. https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/our-backyard-not-chinas Online Accessed: April 15th, 2022

[34] Anna Powles and Joanne Wallis. “It’s time to talk to, not at, the Pacific.” The ASPI Strategist. 2022. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/its-time-to-talk-to-not-at-the-pacific/

Online accessed: 4th April 2022

[35] Powles and Wallis. “It’s time to talk to, not at, the Pacific”, 2022.

[36] Powles and Wallis. “It’s time to talk to, not at, the Pacific”, 2022.

[37] Evan Wasuka and Toby Mann. “Federated States of Micronesia calls on Solomon Islands to reconsider security treaty with China.” ABC News. 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-31/federated-states-micronesia-solomon-islands-china-security/100955650 Online Accessed: April 4th, 2022

[38] Patricia O’Brien. “The ‘Framework Agreement’ with China Transforms the Solomon Islands into a Pacific Flashpoint”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, March 31st, 2022. https://www.csis.org/analysis/framework-agreement-china-transforms-solomon-islands-pacific-flashpoint

[39] O’Brien. “The ‘Framework Agreement’ with China Transforms the Solomon Islands into a Pacific Flashpoint”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2022.

[40] Michael Shoebridge. “Djibouti shows what Sogavare’s deal with China really means”. The ASPI Strategist, April 11th, 2022. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/djibouti-shows-what-sogavares-deal-with-china-really-means/. Online Accessed: 8th May, 2022.

[41] Tarcisius Kabutaulaka. “Solomon Islands asserts its sovereignty – with China and the West.” The Interpreter. 2022. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/solomon-islands-asserts-its-sovereignty-china-and-west Online Accessed: April 4th, 2022

[42] Mihai Sora, “Dark days for Honiara in the shadow of geopolitics”. The Interpreter, 25th November 2021. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/dark-days-honiara-shadow-geopolitics

[43] Sora, “Dark days for Honiara in the shadow of geopolitics”. The Interpreter, 2021.

[44] Sora, “Dark days for Honiara in the shadow of geopolitics”. The Interpreter, 2021.

[45] Derek Gwali Futaiasi. “Solomons: Putting a draft security deal with China in local context.” The Interpreter. 2022 https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/solomons-putting-draft-security-deal-china-local-context Online Accessed: April 15th, 2022