Green Hydrogen and Advancing all Pillars of the Australia-Korea Partnership

February 2024 | Abbey Watkin

About the author

Abbey Watkin is a third year Bachelor of Arts student, with double majors in Political Science and International Relations, and Korean Studies. After University, Abbey is passionate about pursuing a diplomatic career, with a focus on the Indo-Pacific, to bridge these two disciplines together.

The Korea-Australia bilateral partnership has underperformed in its security and People-to-People (P2P) spheres, compared with its more robust trade and investment connections. Economic complementarity, external security constraints, and mutual cultural oversights, have limited Australian-Korean collaboration to a narrow economic space. Therefore, a trade-based initiative is best placed to advance this partnership. Green hydrogen collaboration is a potential policy area that can help to strengthen this crucial bilateral relationship. Hydrogen will play a leading role in the global clean energy transition; a joint pursuit into the green hydrogen industry could position Australia and Korea as economic leaders in the Indo-Pacific. Additionally, the opportunities for non-traditional security cooperation, where clean energy intersects with regional aid and development, are also significant. Cultural exchange as a by-product of hydrogen industry collaboration must also be prioritised to enhance the bilateral P2P foundations. Through the lens of green hydrogen cooperation, as an economic-focused policy initiative, there is significant potential to advance all three pillars of this crucial strategic partnership.

Introduction

The diplomatic relationship between the Republic of Korea (henceforth Korea) and Australia recently observed it’s 60th anniversary in 2021. The momentum behind this partnership is still strongly present in foreign policy discourse between the two countries. As similar sized economies with similar GDPs in the Indo-Pacific, Australia and Korea have a lot in common[1]. As middle powers, both nations promote multilateral cooperation, and the rules-based order, as the dominant framework for regional relations[2]. They are both members of the G20, G7 Plus, APEC, EAS and other regional and global fora[3]. Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that they should automatically have a comprehensive and successful bilateral alliance. Australia was the second nation to act in the Korean War, and as mutual allies of the U.S., the relationship has been characterised by goodwill and friendliness since[4]. In 2021, the relationship was upgraded to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership[5]. This is, primarily, a reflection that their trade relationship is one of Australia’s most important in the region[6]. Despite these many presumptions that Australia and Korea must have a highly advanced relationship, they really act as “peers not partners”[7]. The common ground and responsibility they share as middle powers, while positive, is not enough to sustain a well-rounded partnership[8]. Both nations are adept at developing strong relationships with smaller economies, or regional superpowers, however, they are less successful in engaging laterally, with each other[9]. In the Indo-Pacific, Korea and Australia act alongside each other, yet do not truly engage with each other[10].

It is essential for Australia and Korea to improve the depth of their bilateral engagement in a time of regional turmoil[11]. With the unpredictability of U.S. regional presence, and a shared vulnerability to economic overdependencies, Australian and Korean interests are converging significantly[12]. This relationship is at a critical juncture, with the elections of President Yoon Suk-Yeol and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese coming off the back of the upgrade to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) in 2021[13]. Yoon has emphasised that Australia and the Indo-Pacific are among the administration’s main priorities [14]. The recent new Korea-US-Japan trilateral launched in 2023 reflects that this new government is willing to go beyond Korea’s traditional and historical constraints and pursue its own security strategy [15]. Yoon’s new Indo-Pacific strategy, a first for Korea, is aimed at diversifying partnerships, providing the perfect opportunity for Australia [16].

Considering this partnership’s narrow economic focus, a trade-based strategy is best-placed to rejuvenate not only the economic pillar of this relationship, but potentially the security and People-to-People (P2P) pillars as well. Green hydrogen cooperation, and its engagement implications for all three pillars of the Korea-Australia partnership, will now be explored.

A Narrow Approach to Bilateral Engagement

The inconsistency between Korean-Australian engagements economically, compared to underperforming security and P2P relations, suggests that this relationship is dominated by a narrow economic focus. Korea is Australia’s fourth largest trading partner, a large source of foreign investment, and undoubtedly critical to the Australian economy[17]. The Korea-Australia Free Trade Agreement (KAFTA) allows over 99% of Australian goods to enter Korea as duty free or with preferential access[18]. Despite this, the broader nature of the Korea-Australia relationship falls behind in comparison to Australian relations with other key regional partners[19]. The strength of their trade relations has been underpinned by a natural economic complementarity – with Australia exporting raw materials and importing Korean technological products. Consequently, diplomatic discourse around this partnership has been diminished [20]. A strong trade compatibility, while it has helped this relationship to advance, has also led to its neglect outside of the economic sphere.

Diplomatic security constraints also contribute to an overreliance on trade-related issues in the discourse of the Korea-Australia partnership. Preoccupation with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (henceforth North Korea), and a degree of economic reliance on China in the background of a security alliance to the U.S., impinges on Korea’s capacity to act decisively in regional security matters[21]. For example, Korea’s hesitancy to take part in the Indo-Pacific narrative until recently, is partly explained by the fact that China perceives Indo-Pacific institutions and minilateralism as U.S.-led encirclement[22]. Korea’s diplomatic scope is diminished, and thus it approaches regional issues predominantly through an economic lens. Korea’s response to China’s economic coercion and monopolisation of supply chains is to pursue economic partnership diversification and supply chain security[23]. Korea therefore prioritises trade relations over security links[24]. While Korea shares Australia’s concerns over China, they have yet to significantly push back in a security capacity [25].

Many saw the visit of the Korean Defence Minister, Lee Jong-sup, to Australia in 2022 as evidence of a budding strategic relationship, however it has been asserted that it was more realistically a business trip to seek further defence industry opportunities for Korean products in the Australian market[26]. Korea likely views Australia as merely a link in their regional supply chain, a willing customer, instead of a security partner[27]. While Australia is the only country apart from the U.S. with whom Korea holds an annual 2+2 (defence and foreign) ministerial level dialogue, these meetings have yet to produce any promising results[28]. Australia has yet to enter a minilateral or bilateral security partnership with Korea, as it has done with Japan and India[29]. From both sides, allocation of diplomatic resources towards security relations have lacked impetus[30]. Overall, it remains that the Australia-Korea partnership is grounded in complementary economies, with inconsistent and insufficient progress in the security sphere.

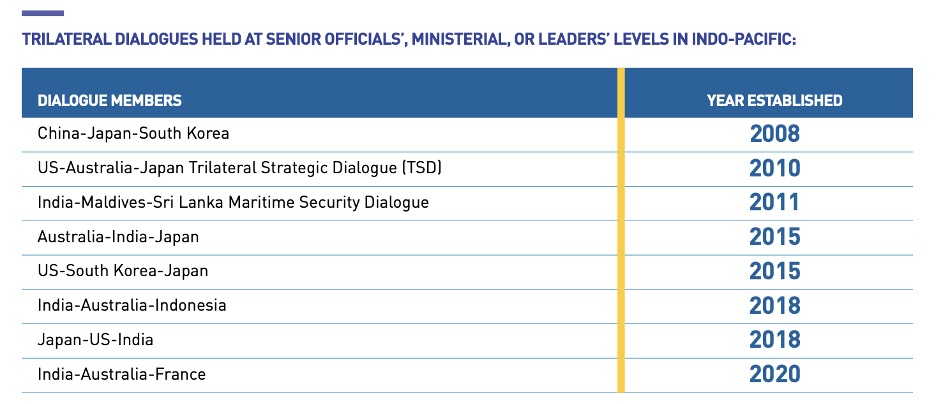

Figure 1: Minilateral structures in the Indo-Pacific Region. Source: Peers Not Partners, Kyle Springer, Perth USAsia Centre (2021).

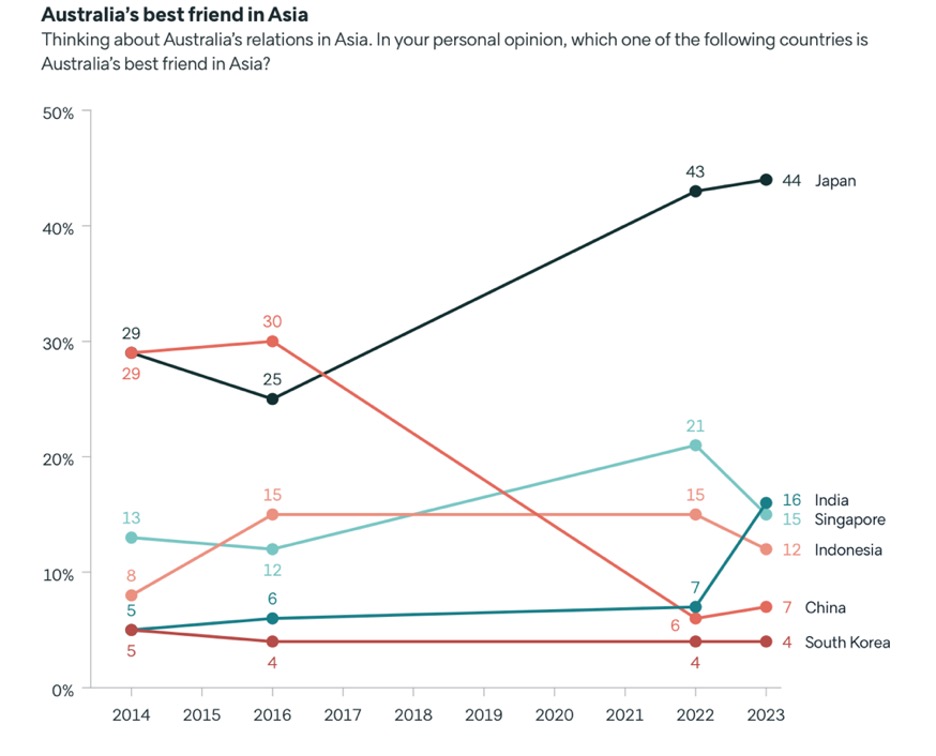

The economic priorities of Korean-Australian bilateral relations have also led to the neglect of the people-to-people (P2P) pillar of this partnership. In the absence of organic cultural ties, the government responsibility to foster stronger P2P links has been neglected[31]. In 2023, only 4% of Australians considered Korea to be their closest ally in Asia (compared to 44% in favour of Japan, and 7% in favour of China)[32]. And this has been a consistent result for the past decade, which highlights the neglect Korea faces in Australian foreign policy discourse. Australia narrowly views Korea predominantly in the context of North Korea and consequently, fails to acknowledge the importance of Korea and its agency in influencing regional geopolitics[33]. This is against the background of Australia’s closer P2P engagement with Japan and the recent emergence of Japan as a regional hub for minilateral security relations, which may alienate Korea[34]. This oversight is mutual, however – there is only one Australian studies centre in Korea, compared to the multiple blossoming institutions in China and Japan[35]. Korea’s lack of P2P-level knowledge of Australia, places Australia firmly in the shadow of the U.S.[36]. When a bilateral relationship has weak P2P links, the populations’ perceptions of illegitimacy and unimportance, regarding the alliance, severely undermine cooperation efforts[37].

Figure 2: Australian attitudes towards different countries in the Indo-Pacific. Source: Lowy Institute Poll (2023).

Green Hydrogen: Too Optimistic?

Bilateral green hydrogen and clean energy cooperation is a potential lens through which to pursue deeper engagement; it can target all three pillars of the Korea-Australia relationship. Green hydrogen could even spark the transition from ‘peers’ to ‘partners’. It not only adds a new element to the economic partnership, but also spurs broader regional implications[38]. Green hydrogen is hydrogen fuel produced with zero carbon emissions and can be used instead of fossil fuels to produce other green commodities, such as steel and aluminium[39]. Both Australia and Korea have 2050 net zero targets in place and prioritise the clean energy transition[40]. The Indo-Pacific region is the centre of the global shift towards low and zero emissions energy, and Australia and Korea have the potential to lead this transition[41].

The realistic potential of green hydrogen collaboration between Korea and Australia is underpinned by the pre-existing structures for a green hydrogen industry in both countries and clean energy partnerships already in place. Australia and Korea were the second and third countries in the world to introduce national hydrogen strategies, following Japan[42]. In Australia, the 2019 National Hydrogen Strategy targets regional Indo-Pacific markets and aims for Australia to become a top 3 hydrogen exporter by 2030[43]. In Korea, the Hydrogen Economy Roadmap, also released in 2019, aims for Korea to be the world’s leading hydrogen economy by 2040[44]. The primary goals of these two strategies are complementary in nature and would energise cooperation between Australia and Korea. Additionally, the Korean private sector is well-positioned for entering the green hydrogen market. Korean companies are organising into hydrogen-focused partnerships, which present Australian firms with enticing commercial opportunities[45]. Furthermore, 15 major Korean companies, at the H2 Business summit in 2021, have pledged an estimated combined AUD$50 billion towards the hydrogen economy by 2030[46].

Government-to-government energy industry cooperation has a strong pre-existing model of joint resource development in place to facilitate hydrogen cooperation – in which, Korean buyers provide investment in return for Australian supply – with successful returns in the coal, iron ore, lithium, and natural gas sectors[47]. On top of this, the 2021 Low and Zero Emissions Technology Partnership focuses on clean hydrogen and clean ammonia technology, low emissions steel and iron ore, carbon capture/utilisation, and hydrogen trade systems[48]. The pre-existing Joint Committee for Energy and Mineral Resources has also been signalled as a useful mechanism to guide the progress of the partnership[49]. The 2021 CSP also expands on clean energy cooperation[50]. Furthermore, the Australia-ROK Science and Technology Bridge is a good example of how to enable cooperative green hydrogen research[51]. Green hydrogen is well positioned as a feasible and realistic policy solution.

While the new green hydrogen industry presents many hurdles to Australian, and Korean, government and business, there is already evidence of significant progress in this new partnership. Unfortunately, global competition in the hydrogen industry is increasing and there are many other nations now pursuing green hydrogen initiatives[52]. Cost competitiveness is critical; hydrogen production in Australia costs 3 times as much as the current cost of energy[53]. Australia lacks the onshore facilities to compete effectively in the midstream of the value chain, dominated by China[54]. Additionally, transporting liquid hydrogen long distances, which requires keeping it at extremely low temperatures, is costly and difficult{55}. Significant funding, research, and innovation is still required to position Australia and Korea as leaders of the new green hydrogen industry[56]. However, there have been significant leaps forward. In 2022, the world’s first trans-continental liquid hydrogen export, in a purpose-built vessel, was conducted between Australia and Japan[57]. Australia must seek to carry on this innovative momentum with Korean partners.

The Korean firm POSCO is a leader in green hydrogen production and has signed low emissions partnerships with large Australian mining companies[58]. POSCO was granted land by the Western Australian government in 2023 to build a hydrogen fuelled green steel plant, which eliminates the liquid hydrogen transportation logistics in producing and using the green hydrogen within the same vicinity[59]. In 2023, Korean firm KEPCO, and Australian Western Green Energy Hub, signed a Memorandum of Understanding to develop one of the largest Australian green hydrogen hubs, covering approximately 15,000 square kilometres[60]. Korea Zinc’s Australian firm Sun Metals also owns a green hydrogen plant in Queensland, Australia, which when completed will export an estimated 500,000 tonnes of hydrogen to Korea and other customers[61]. Despite potential future difficulties in pursuing Korea-Australia cooperation in green hydrogen, it is undeniable that recent joint projects illustrate the potential and momentum of this industry going forward.

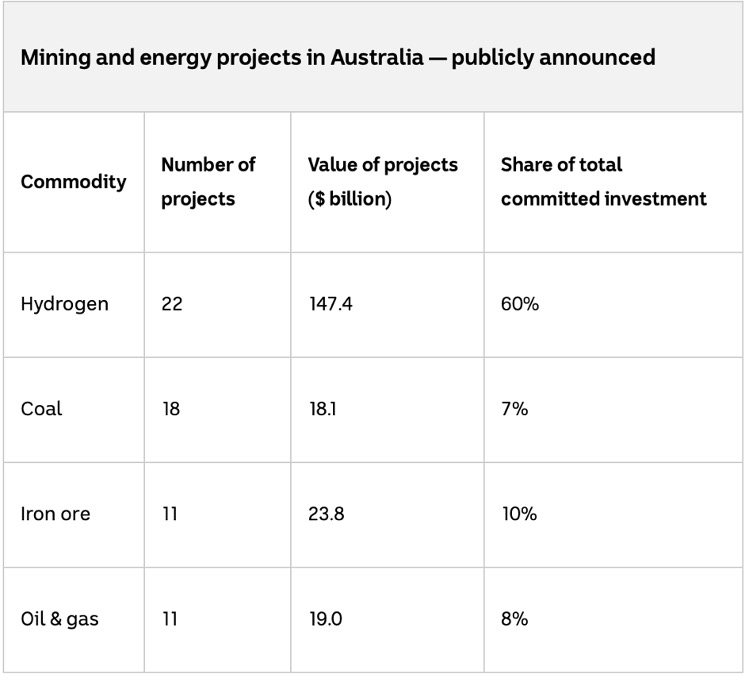

Figure 3: Prospective hydrogen energy projects in Australia, compared to other mining and energy commodity projects. Source: ABC News (2023). Adapted from: Commonwealth Bank Australia (2023).

Addressing the Three Pillars of the Relationship

Australia-Korea green hydrogen and clean energy collaboration will promote economic stability and progress in a period of global energy transitions. Individually, both Korea and Australia foresee a significant boost to their economies if their national hydrogen strategies are successfully implemented. Korea expects an injection equivalent to 2.5% of the 2017 GDP by 2040, and the creation of at least 420,000 jobs[62]. Australia estimates a minimum GDP growth of AUD$11 billion a year by 2050, or up to AUD$26 billion[63]. In a global shift from fossil fuel reliance to clean energy, Korea and Australia have the potential to be at its forefront, reaping the economic benefits[64]. And green hydrogen in particular, will lead the clean energy sector[65]. It is essential for Australia to pursue a leadership role in the new hydrogen industry, in order to maintain its notable dominance in the international energy sector when fossil fuel exports are phased out[66]. Korea’s private sector is already leading the region’s clean energy market and is one of the first global demand hubs[67].

With complementary economies, Australia with global upstream dominance, and Korea with a significant downstream presence, in the clean energy value chain, the division of labour can also be mutually beneficial[68]. There are significant innovative benefits from this collaboration, as clean energy technology is pursued. Industrial innovation is the new arena for global competition[69]. Both countries will benefit from preventing China, or others, from monopolising new technology in the clean energy sector[70]. Moreover, both nations can pursue economic stability through diversifying their energy trade partners and increasing resilience against economic coercion[71]. Given their complementarity, Korea and Australia are ideal partners in the pursuit of this mutual goal[71]. Regional supply chain economic partnership opportunities will be significant – regional industrialising countries will be interested in technological or investment assistance in their entry to the clean energy value chain[73]. Finally, as an economic-based strategy, it is better positioned to enhance the trade-dominant bilateral partnership between Australia and Korea.

Green hydrogen cooperation will also have considerable strategic benefits in the defence and security pillar of the Australia-Korea bilateral relationship. Aiming to directly enhance the traditional security aspects of their relationship, through issues such as North Korean or Chinese relations, may prove difficult in improving security relations as a whole[74]. Steering bilateral cooperation towards non-traditional security aspects, economics, and cultural links, will likely be more effective[75]. Moreover, to promote increased long-term regional security engagements, reducing Korea’s dependence on China will be essential. A green hydrogen partnership will increase energy supply chain resilience and avoid disruptions to trade and energy supply, which are a significant component of defence coordination[76]. Currently, China is monopolising the strategic benefits of supply chain dominance[77]. Korean, and Australian, foreign policy and security constraints associated with vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion, which have hampered bilateral relations in the past, will be lessened.

Regionally, the potential for non-traditional security collaboration in clean energy infrastructure investment is glaring[78]. Similar to Australia, Korea’s development assistance budget is large and growing, at AUD$4.9 billion in 2022[79]. Australia and Korea are already engaged actors in aiding industrialising economies in Southeast Asia[80]. Thus, they are well positioned to lead infrastructure and development assistance in the form of clean energy. This will strengthen the capacity of regional nations to resist the potential weaponisation of economic resources[81]. Developing equitable regional supply chain systems, led by Korea and Australia, will be critical to regional stability[82]. Vietnam is one example, where Australia and Korea are major exporters and investors respectively[83]. Situations such as this, where Australian and Korean regional economic interests coincide, could be utilised to improve security frameworks. Two major areas, which would produce fruitful cooperation between Australia and Korea, are regional aid, and green technology[84]. Green hydrogen, meeting regional aid and development, can be complementary to emerging economies, and can meaningfully contribute to regional defence and security.

The P2P sector of the Korea-Australia partnership, green hydrogen has enormous potential to improve the strength of cultural relations. The oversight of P2P links has had a debilitating effect on this partnership and therefore, despite green hydrogen cooperation being primarily an economic engagement strategy, implications for P2P must also be considered. Firstly, enabling joint research and innovation in the green hydrogen industry requires the exchange and interaction of researchers, students, experts, and innovators[85]. Moreover, there is a need to involve the private sector increasingly in bilateral hydrogen cooperation[86]. This will lead to an exchange between industrial workforces and will facilitate substantial cultural interconnection. Currently, Australia-Korea migration has significant hurdles for entry into both nations. Australia has more seamless expatriate and visa systems with Hong Kong, Singapore, and other regional partners[87]. Visa processing fees, wait times, and eligibility criteria are among the mutual burdens on prospective Australian and Korean migrants[88].

Korean migration to Australia is small-scale compared to Indian or Chinese migration[89]. This underperformance is unfortunate, as expatriate communities have significant untapped potential to contribute to P2P links[90]. Visa reform is direly needed to advance cultural, and trade, links between Korea and Australia[91]. Therefore, both nations should address these migratory barriers to improve green hydrogen’s ability to contribute to better P2P outcomes. Additionally, Australia must increase discourse around Korea in regional communities, where green hydrogen activities usually take place[92]. Australian regional communities do not distinguish the economic footprint of Korea from that of China or Japan[93]. In return, Korean firms should seek knowledge surrounding Australian Indigenous and First Nations populations to ensure sustainable social practice in Australia[94]. This mutual learning and understanding process is another by-product of green hydrogen cooperation which improves P2P cultural connections between Australia and Korea.

Conclusion

Bilateral green hydrogen cooperation between Australia and Korea has the potential to advance this relationship into a stronger economic, security, and P2P partnership. While traditionally, Korea-Australia relations have been constrained to trade-related concerns, the green hydrogen economic initiative has the potential to expand upon these narrow foundations. While promoting clean energy industry leadership, green hydrogen cooperation can also positively affect regional defence and security through aid and development. The pursuit of this will also expand the P2P links between Australia and Korea. Korea-Australia diplomatic policy should target green hydrogen cooperation, and must also specifically support all three pillars of this bilateral relationship if the true potential of Korean-Australian relations are to be realised.

Conclusion

To advance the Korea-Australia relationship to a well-rounded, successful partnership, policy makers should:

- Approach green hydrogen cooperation as a new lens for advancing the economic partnership between Australia and Korea. This new industry has the potential to solidify Australia and Korea’s place as economic, and clean energy, leaders in the Indo-Pacifica, and provide fruitful trade and innovation returns. Given this partnership’s narrow economic focus, a trade-based strategy is more likely to successfully deepen bilateral engagement.

- Pursue joint Korea-Australia regional aid and development initiatives, through green hydrogen, to promote stability and supply chain security. Korean-Australian leadership of regional green hydrogen supply chains will improve resilience against Chinese resource and energy weaponization. The implications for non-traditional defence and security collaboration are substantial.

- Encourage the P2P by-products of green hydrogen industry cooperation to strengthen the foundations of the Korea-Australia bilateral relationship. Less restrictive visa policies should be introduced to encourage cultural exchange in the pursuit of collaborative green hydrogen technological innovation enhancement. Cultural interconnections between Korean investors, Australian communities, and the broader populations of both nations should be fostered and advanced.

Reference List

[1] Kyle Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership,” Perth USAsia Centre, June 16, 2021, https://perthusasia.edu.au/research-insights/publications/peers-not-partners-towards-a-deeper-australia-korea-partnership/

[2] Gareth Evans, “A Better Rules-Based Order: What Australia and Korea can do together,” Asialink, May 3, 2023, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/a-better-rules-based-order-what-australia-and-korea-can-do-together

[3] James Cotton, “Middle Powers in the Asia Pacific: Korea in Australian Comparative Perspective,” Korea Observer 44, no. 4 (2013): 593-621, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/middle-powers-asia-pacific-korea-australian/docview/1655874588/se-2

[4] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[5] Government of Australia, “Australia-Republic of Korea Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d.), https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/republic-of-korea/republic-korea-south-korea/australia-republic-korea-comprehensive-strategic-partnership

[6] Government of Australia, “Republic of Korea Country Brief” (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d.), https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/republic-of-korea/republic-of-korea-country-brief#economic-overview

[7] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[8] Jeffrey Robertson, “A Window of opportunity in Australia-Korea Relations?,” Australian Institute of International Affairs, April 22, 2022, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/window-of-opportunity-australia-korea-relations/

[9] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[10] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[11] Brendan Taylor, “The Korean Peninsula as a security flashpoint,” University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, September, 2021, https://defenceuwa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Black-Swan-Strategy-Paper-Issue01_ROK-AUS.pdf

[12] William Tow and Ajin Choi, “Facing the crucible: Australia, the ROK, and cooperation in Asia,” Korea Observer 42, no. 1 (2011): 1-19

[13] Peter K Lee, “Déjà vu for Australia-Korea relations,” Asialink, May 26, 2022, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/deja-vu-for-australia-korea-relations

[14] Jeffrey Robertson, “A Window of opportunity in Australia-Korea Relations?”

[15] Afeeya Akhand and Alex Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 26, 2023, https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2023-10/SI184%20Where%20next%20for%20Australia%20and%20South%20Korea.pdf?VersionId=E5Bz1rsumBlwQ1Mbnbs3A.3ajr6Q6oTT

[16] Peter K Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges,” Korea-Australia Relations Project, July, 2023, https://www.thekarp.net/_files/ugd/29648b_3f86af4ae6314858af35a3bbe29f8a29.pdf

[17] Wongi Choe, “Australia and Korea: Middle Powers in Uncharted Waters,” Asia Society, November 22, 2021, https://asiasociety.org/australia/australia-and-korea-middle-powers-uncharted-waters

[18] Government of Australia, “KAFTA and trade in goods” (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d.), https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/kafta/fact-sheets/kafta-and-trade-in-goods

[19] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[20] Jeffrey Robertson, “A Window of opportunity in Australia-Korea Relations?”

[21] Jae Jeok Park, “South Korea-Australia security cooperation: The fine line between enhancement and friction in East Asia,” University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, September, 2021, https://defenceuwa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Black-Swan-Strategy-Paper-Issue01_ROK-AUS.pdf

[22] Evans, “A Better Rules-Based Order: What Australia and Korea can do together.”

[23] Lauren Richardson, “Moon’s visit is no coup for the China hawks,” Asialink, December 17, 2021, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/moons-visit-is-no-coup-for-the-china-hawks

[24] Hayley Channer, “Reinvigorating Australia-ROK security cooperation,” University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, September, 2021, https://defenceuwa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Black-Swan-Strategy-Paper-Issue01_ROK-AUS.pdf

[25] Richardson, “Moon’s visit is no coup for the China hawks.”

[26] Jeffrey Robertson, “Australia-Korea Relations about commerce, not strategy,” Asialink, August 18, 2022, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/australia-korea-relations-about-commerce,-not-strategy

[27] Robertson, “Australia-Korea Relations about commerce, not strategy.

[28] William Paterson, “Australia and Korea: Defence and security,” University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, September, 2021, https://defenceuwa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Black-Swan-Strategy-Paper-Issue01_ROK-AUS.pdf

[29] Channer, “Reinvigorating Australia-ROK security cooperation.”

[30] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[31] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[32] Ryan Neelam, “Lowy Institute Poll 2023,” Lowy Institute, June 21, 2023, https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/files/lowyinsitutepoll-2023.pdf

[33] Jeffrey Robertson, “Australia’s South Korea problem,” Asialink, January 12, 2023, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/insights/australias-south-korea-problem

[34] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[35] Robertson, “Australia’s South Korea problem.”

[36] Paterson, “Australia and Korea: Defence and security.”

[37] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[38] James Bowen and Kyle Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership,” Perth USAsia Centre, March, 2022, https://perthusasia.edu.au/research-insights/publications/strategic-energy-the-emerging-australia-korea-hydrogen-partnership-2/

[39] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[40] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[41] James Bowen, “Reenergising Indo-Pacific Relations: Australia’s Clean Energy Opportunity,” Perth USAsia Centre, July, 2022, https://puac-wp-uploads-bucket-aosudl-prod.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/03143710/Reenergising-Indo-Pacific-relations-Australias-clean-energy-opportunity.pdf

[42] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[43] Government of Australia, “Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy,” (Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, November 2019), https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-national-hydrogen-strategy.pdf

[44] Government of the Republic of Korea, “Hydrogen Economy: Roadmap of Korea,” (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, 2019), https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/45185a_fc2f37727595437590891a3c7ca0d025.pdf

[45] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[46] Byung-wook Kim, “Tycoons unite for hydrogen future,” The Korea Herald, September 8, 2021, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210908000791

[47] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[48] Government of Australia, “Australia’s international clean energy partnerships,” (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, n.d.), https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/international-climate-action/international-partnerships#korea

[49] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[50] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[51] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[52] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[53] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[54] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[55] Rachel Pupazzoni, “Australian hydrogen in demand as South Korean manufacturers look to reach renewable energy target by 2050,” ABC News, May 15, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-15/south-korea-hydrogen-clean-energy-manufacturing-australia/102345294

[56] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[57] Government of Australia, “State of Hydrogen: 2022,” (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, 2022), https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/state-of-hydrogen-2022.pdf

[58] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[59] Pupazzoni, “Australian hydrogen in demand as South Korean manufacturers look to reach renewable energy target by 2050.”

[60] Government of Australia, “KEPCO and WGEH – Net zero, Hydrogen,” (Australian Trade and Investment Commission, August 2, 2023), https://www.globalaustralia.gov.au/success-stories/kepco-and-wgeh-net-zero-hydrogen

[61] Pupazzoni, “Australian hydrogen in demand as South Korean manufacturers look to reach renewable energy target by 2050.”

[62] Government of the Republic of Korea, “Hydrogen Economy: Roadmap of Korea.”

[63] Government of Australia, “Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy.”

[64] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[65] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[66] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[67] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[68] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[69] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[70] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[71] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[72] Choe, “Australia and Korea: Middle Powers in Uncharted Waters.”

[73] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[74] Jae Jeok Park, “Security Cooperation between South Korea and Australia: Bilateral for Minilateral?,” Pacific Focus 31, no. 2 (2016): 167-86, https://doi.org/10.1111/pafo.12069

[75] Springer, “Peers not Partners? Towards a deeper Australia-Korea Partnership.”

[76] Choe, “Australia and Korea: Middle Powers in Uncharted Waters.”

[77] Bowen, “Reenergising Indo-Pacific Relations: Australia’s Clean Energy Opportunity.”

[78] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[79] Government of Australia, “Republic of Korea Country Brief.”

[80] Jiye Kim and Arpit Raswant, “Australian perspective on engaging with South Korea in the Indo-Pacific,” Asian Politics and Policy 15, no. 1 (2023): 48-62, https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12672

[81] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[82] Bowen, “Reenergising Indo-Pacific Relations: Australia’s Clean Energy Opportunity.”

[83] Bowen and Springer, “Strategic Energy: The emerging Australia-Korea hydrogen partnership.”

[84] Cotton, “Middle Powers in the Asia Pacific: Korea in Australian Comparative Perspective.”

[85] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[86] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[87] Jeffrey Robertson, “Australia-Korea: Sixty years of benign neglect,” University of Western Australia Korea Research Centre, November, 2021, https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/toward-deeper-engagement-prospect-and-reflections-on-the-60th-ann

[88] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[89] Akhand and Bristow, “Where next for the Australia-South Korea partnership?”

[90] Robertson, “Australia-Korea: Sixty years of benign neglect.”

[91] Bronwen Dalton, “Six ways to boost the Australia-Korea Trade Relationship,” University of Western Australia Korea Research Centre, November, 2021, https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/toward-deeper-engagement-prospect-and-reflections-on-the-60th-ann

[92] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[93] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”

[94] Lee, “Expanding Australia-Korea People-to-People Exchanges.”