Then and Now: Why the Future Defence of Australia Requires a New Force Posture Review

7 December 2021 | Marcus Schultz

Executive summary

The release of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update marked an important shift away from the strategic and capability judgements outlined in the 2012 Force Posture Review. In coming years, the existing level of military preparedness to defend in Australia’s north-western maritime approaches is more likely to be tested. While Defence has made some commendable progress toward improving strategically important mainland and offshore Australian Defence Force (ADF) bases in the north and north west, inconsistencies remain raising the risk level and likelihood of key operational and strategic needs being overlooked and under-addressed.

There currently exists a window of opportunity for the federal Government to signal its commitment to conduct a new force posture review. This policy adjustment should accommodate developments in the AUKUS pact and Gascoyne Gateway deep-water port proposal to advance Australia’s interests and strengthen the capability of the ADF to operate flexibly in a rapidly deteriorating strategic environment.

Policy recommendations

- The Australian Government should signal its commitment to conduct a new force posture review to bridge the various departmental and jurisdictional silos which place clear limitations on synergistic defence planning in a time of heightened uncertainty.

- A new force posture review should focus attention on the growing strategic need to defend Australia’s extensive maritime approaches.

- Defence should review Project 8219, Air 555 and Air 7000 various works projects underway regarding the P8-A Poseidon, MQ-4C Triton and MC-55A Peregrine aircraft to address inconsistencies.

- The federal Government and ADF should leverage the lead times of the Gascoyne Gateway port proposal and AUKUS security pact to reassess current and future sovereign capability needs.

Introduction

The strategic and capability judgements of the 2012 Australian Defence Force Posture Review have been superseded by the release of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update (DSU). The expectation that the ADF is only likely to be tasked with humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and security and stabilisation operations in the immediate region is no longer sound guidance for defence planning

The DSU noted that the ADF must be able to adjust military capability and preparedness in response to new challenges posed by major power competition, coercion, grey-zone activities and accelerating regional military capabilities.[1] The Australian Government should follow through on the DSU with a focus on Australia’s north western maritime approaches to ensure the ADF is correctly geographically positioned to carry out its new mandate. A new review into ADF force posture is now required.[2]

This briefing paper provides some background to the recent history of the defence relationship with the north west of Australia, an overview of the geostrategic risks currently facing WA and the nation, and an assessment of current projects for increasing the visible presence of the ADF in the immediate region.

Updated strategic guidance and implications for the ADF

On 3 May, 2012, Prime Minister Julia Gillard and Minister for Defence Stephen Smith released the final report of the Defence Force Posture Review—the first in over a quarter of a century. The review fed into the economic, security and strategic considerations of the 2013 Defence White Paper, which emphasised the role of the ADF in securing the littoral approaches to the north west of Australia.[3] It noted that:

An effective, visible force posture in… [Australia’s] northern and western approaches is necessary to demonstrate our capacity and our will to defend our sovereign territory, including our offshore resources and extensive maritime areas.[4]

The 2012 Review concluded that whilst the emphasis on conducting humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations in Australia’s immediate neighbourhood and stabilisation operations in the South Pacific and East Timor did not warrant widespread changes in the location of ADF bases, ‘force posture need[ed] to be adjusted to meet current and future needs.’[5] Specifically it outlined that:

Defence should upgrade Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Learmonth to enable protracted, unrestricted operations by KC-30 and P-8 aircraft; upgrade the Cocos (Keeling) Islands airfield facilities to support unrestricted P-8 and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operations (and KC-30 operations with some restrictions); enhance… preparedness for operations in the north west through joint exercises… more simulated exercises and ‘wargames’… and increased aircraft and ship visits to airfields and ports; and a program of senior officer and staff study visits… to improve awareness and familiarity with the north west.[6]

Between 2021 and 2020 Australia’s strategic environment has rapidly deteriorated. At the release of the DSU the Prime Minister Scott Morrison noted that Australia was confronting ‘one of the most challenging times we have known since the 1930s and the early 1940s.’[7]

Whilst the role of the ADF across this period remained focused on deterring and defeating armed attacks on or threats to Australia,[8] in a highly significant move the DSU removed the 10-year timeframe forewarning a major conventional conflict in the region.[9] Accordingly, the DSU tasked the ADF to be prepared to respond to the prospect of high intensity military conflict in the Indo-Pacific with credible force if necessary.[10] This outline of Australia’s strategic environment stands in stark contrast to the requirements outlined in the 2012 Force Posture Review.

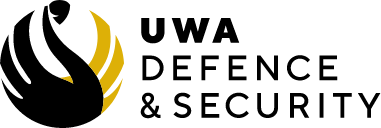

The significance of the North West to Australia’s security and sustainment

There are cogent reasons why the federal Government should concentrate upon the effective control and defence of the north west of Australia. This region is home to three of Australia’s six basins available for offshore oil and gas exploration and the majority of crude oil, condensate and liquefied natural gas (LNG) acreage areas.[11] As of September 2021, WA’s oil and gas sector had minerals and petroleum projects in the pipeline valued at an estimated $127 billion.[12] Of that, $91 billion were invested planned and possible projects, and $36 billion in projects committed or under construction. As Australia’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China remains strained and strategic competition between the PRC, the US and its allies intensifies, it is noteworthy that these critical oil and gas fields are, today, now within striking distance of approximately 350 DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missiles deployable by the People’s Liberation Army (Figure 1). This also highlights the vulnerability of key shipping lanes that transit the eastern Indian Ocean.[13]

Figure 1: A move by China’s PLA from medium-range to long-range missiles will change the reach and balance of air and maritime power in the western Pacific. Source: Lowy Institute

Australia’s north western regions are our largest producers of hydrocarbons. In 2019-20, Western Australia produced 121 million barrels of crude oil and condensate or 80 percent of the national output, and 13 percent of global LNG volumes.[14] These natural resources are extremely important to the national economy and key regional trading partners in the Indo-Pacific. In 2020, minerals and natural gas exports from WA comprised the bulk of the state’s $187 billion contribution to the Australian economy—and more than half the national total.[15] Additionally, much of Australian LNG shipped from ports in North West WA is essential for Japanese and South Korean baseload electricity generation.[16] Any disruption to these trade routes would result in a minimum 25 percent loss of carrying capacity.[17] Australia’s commercial trade routes are critical strategic pathways,[18] and should be regarded as critical vulnerabilities in the supply chains of emerging renewables export opportunities such as hydrogen.

Though the possibility of a direct attack is remote, the protection of sea lanes and maritime transit to and from Australian territorial waters was not canvassed in the DSU. Importantly, Australia’s oil dependence and vulnerability has only increased since 2012, with three of Australia’s seven onshore oil refineries having closed. This represents a 42 percent decline in domestic oil refining capacity.[19] Additionally, Australia has not been able to meet its 90-day oil stockholding obligation as required set by the International Energy Agency. This worrisome trend is only projected to deteriorate. A recent study found that by 2030, Australia will likely have no domestic crude oil refineries and will be entirely dependent upon transport fuel (petrol, diesel and jet fuel) imports,[20] and hold less than 22 days of fuel reserves.[21]

The Australian Government has developed a fuel security package to reinstate full compliance by 2026. As part of the compliance plan, Australia will hold physical oil stocks in the United States.[22] However, the lack of access to a sovereign fuel storage reserve would severely limit the capability of the ADF to deploy and sustain a substantial combat force in an emergency.

It has been argued that as petrol, diesel and jet fuel stocks bound for Australian ports are not counted toward the obligation, ‘the decline… raises no heightened supply risk for the domestic fuels market or for fuel users.’[23] However, a recent report from the Australian Naval Institute and the Naval Studies Group of the University of New South Wales (Canberra) reached the conclusion that Australia is not well positioned to defend its trade and essential sea supply in a contested environment.[24] This is understandable given that the last time control of the Indian Ocean as was seriously contested was during the Second World War. In that conflict, small air defence and maritime strike forces operating out of RAAF bases in WA and at Cocos (Keeling) Islands protected the country against possible Japanese carrier raids and attacks on allied merchant vessels and submarine patrols.[25] With the Prime Minister having raised the spectre of risks not seen since the 1930s, it is only prudent to reassess these issues in light of the end of the 10-year warning time and the heightened risk of high end conventional conflict. This is more so the case given no comprehensive plans exist to protect merchant shipping in Australian waters or its port precincts.[26] A new force posture review should address disadvantages for the ADF in terms of its preparedness for a prolonged conflict in the defence of our sovereign territory, offshore resources and extensive maritime areas.

Inconsistencies in current force posture initiatives in North West WA

The military and strategic value of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands airfield facilities as a staging location for naval replenishment and maritime air patrol and surveillance activities during a prolonged conflict has not received significant attention since 2012. The practical implications of not having an up-to-date force posture investment program is evident in the problematic progress of upgrades to airfield facilities at Australia’s Indian Ocean territories. Current force posture initiatives to accommodate the P8-A Poseidon surveillance and response aircraft, the MQ-4C Triton autonomous maritime patrol aircraft, and the MC-55A Peregrine electronic warfare plane, have potential to produce inconsistent outcomes.

Defence Project 8219, a $184 million various works initiative to be completed by mid-2023, will improve the airstrip at Cocos (Keeling) Islands to accommodate the operational roles of fifth-generation RAAF aircraft entering into service. The project will strengthen the existing 2,441 metre runway and hardstands, widen the shoulder from 3.5 to 7.5 metres, and provide a new Aeronautical Ground Lighting to support the P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance and response aircraft on deployment from RAAF Base Edinburgh.[27] Considering the 7,500km range of the P-8A Poseidon, its deployment from Cocos (Keeling) Islands would substantially extend Australia’s defensive depth into the Indian Ocean and South China Sea (Figure 2.).

Figure 2: Operational ranges of P-8A Poseidon from RAAF Base Edinburgh and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Source: Author’s own

However, Defence has previously indicated that no P-8A Poseidon aircraft or support personnel will be permanently based at the airfield.[28] This decision potentially limits opportunities for Cocos (Keeling) Islands to sustain the P-8A Poseidon, as well as the P-8I variant operated by the Indian Navy, during joint exercises and maritime surveillance operations in the region.

Other aircraft, such as the MQ-4C Triton high-altitude surveillance drone used by the US Air Force and the RAAF, could potentially benefit from the upgrade. The MQ-4C Triton has an operational range of 15,185kms and is equipped with a sensor suite that provides a 360-degree view of its surroundings for over 2,000kms. Its fuel tank configuration would likely require sun shelters to be built in addition to permanent facilities for the launch and recovery crew and mission control element.[29] These requirements fall outside the scope of Project 8219.

Operational support for the MQ-4C Triton at Cocos (Keeling) Islands could be extended under the Air 555 Phase 1 project. This initiative seeks to accommodate the MC-55A Peregrine Electronic Warfare reconnaissance aircraft, designed to complement the MQ-4C Triton with its 12,500km range. Approved by the federal Government in 2017, the $290 million project will establish RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia as an initial operational facility, and small forward-operating facilities at Townsville and Darwin and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Defence told a Parliamentary Standing Committee in August 2020 that the forward operating facilities would include capacity for data handling, limited operational planning, storage of self-protection flares for operational use and minor aircraft maintenance, with minimal increases in numbers at each location.[30]

Air 555 Phase 1B is proceeding alongside Air 7000 Phase 1B, a program which involves constructing facilities to support the MQ-4C Triton as the platform enters into service in Australia from 2025. Unlike the Air 555 project, Air 7000 Phase 1B overlooks the potential of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands as a forward operating base. According to the Auditor-General’s 2019–20 Major Projects Report, Air 7000 Phase 1B similarly establishes RAAF Base Edinburgh as the main operating base for the MQ-4C Triton and RAAF Tindal as the forward operating base, 320kms southeast of Darwin.[31]

Despite commonalities between the P-8A Poseidon, MQ-4C Triton and MC-55A Peregrine platforms, the upgrades at Cocos (Keeling) Islands to support P8-A Poseidon operations do not necessarily allow the airfield to support MQ-4C Triton operations.[32] It is unclear whether the introduction of the MC-55A Peregrine forward operating base will indirectly enable this capability.

An airstrip capable of accommodating the P-8A Poseidon, MQ-4C Triton and MC-55A Peregrine would allow Australia to patrol a wider area in the Indian Ocean and regions such as the South China Sea. The siloing of these projects highlights the ongoing infrastructure, operational and strategic risks for the ADF operating without an up to date force posture directive.

Given new strategic partnerships being formed through initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between the US, Australia, India and Japan, AUKUS, and the US having just completed a Global Force Posture Review which included a focus on more force deployments to Australia, a new Australian force posture review would help to identify and align regional engagement. This includes potential base sharing arrangements between Canberra, Washington, and New Delhi. This could also include new force posture initiatives outlined in the AUSMIN 2021 communique such as a combined logistics, sustainment, and maintenance enterprise to support high‑end warfighting and combined military operations in the region.[33]

Planned and coordinated upgrades to facilities like those on Cocos (Keeling) Islands, driven by a force posture review outcome, have the potential to effectively support new and innovative military exercises akin to AUSINDEX and Pitch Black, Malabar and Indo-Pacific Endeavour deployments. This could include the rotational deployment of all types of US aircraft in Australia and appropriate aircraft training and exercises, as well as efforts to increase logistics and sustainment capabilities of US surface and subsurface vessels in Australia.[34] The historic announcement that the US and the UK will supply Australia with conventionally-armed nuclear submarines under the AUKUS technology sharing arrangement only adds to the imperative for a new force posture review.

Achieving a more visible ADF presence in the North West

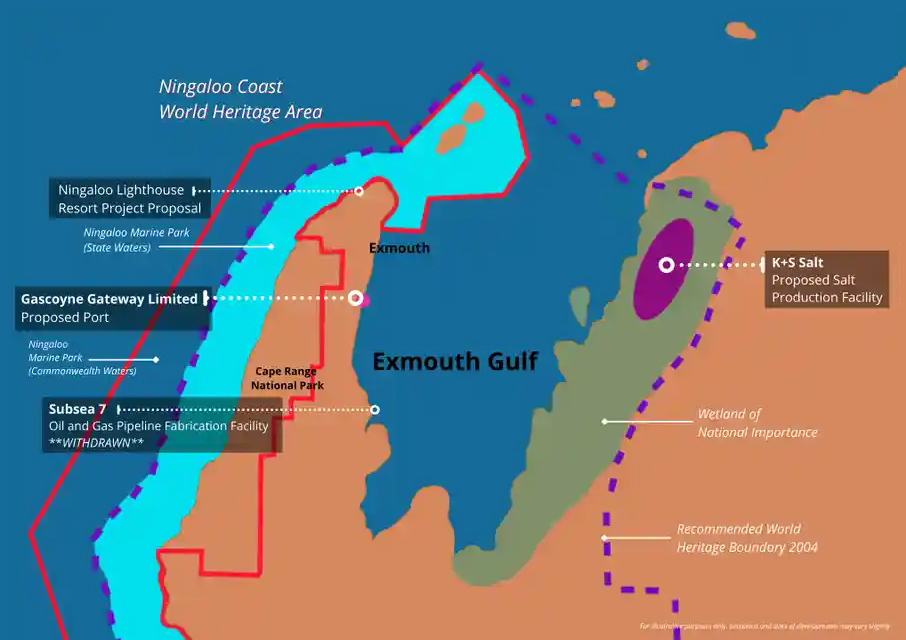

New maritime infrastructure projects in the North West also seek to address these inconsistencies and offer avenues to align Defence planning with the DSU. The Gascoyne Gateway proposal to build Australia’s first carbon neutral deep-water multi-user port precinct 10kms south of Exmouth (Figure 3.) seeks to provide substantial public benefit and strategic value for Defence.

Figure 3: A map showing the proposed development of Exmouth Gulf. Source: Protect Ningaloo

As noted in a submission to the federal Government for inclusion in the 2021-22 budget, Gascoyne Gateway will cater for every Royal Australian Navy and Australian Border Force vessels including patrol boats, landing helicopter dock ships and submarines.[35] It will also provide unrestricted access to a minimum 30-million litre state-of-the-art fuel storage facility to address fuel storage and strategic reserves issues not covered by the Defence Fuel Transformation Program the ADF is currently undertaking to improve the fuel supply chain nationally.[36] Additionally, it will enhance defence cooperation between Australia and the US, including on force posture.[37]

The project’s development blueprint is currently undergoing a rigorous approvals process overseen by the Environmental Protection Authority of WA.[38] If approved, construction will commence in mid-2023 to be completed by 2025 and be operational for 50-100 years. The federal Government can support Gascoyne Gateway through the existing Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility funding mechanism.

Gascoyne Gateway is located 2,125kms from Cocos (Keeling) Islands (28 percent closer than HMAS Stirling) and is closer to one of the most capable airstrips in north-western Australia at RAAF Learmonth.[39] The integration of the Gascoyne project and its military use would improve ADF capability to defend sovereign territory, offshore resources and extensive maritime areas in the North West.

While Gascoyne Gateway aligns with the sovereign capability requirements outlined in the DSU, the ADF has yet to signal a commitment to using the facility if it is built.[40] The ADF could use the lead time to consider the strategic value of Gascoyne Gateway and inform the 18-month consultation process Australia must now undertake to develop and sustain sufficient shipyard and maintenance capacity under the AUKUS security pact.[41] The federal Government could likewise use this window of opportunity to conduct a new force posture review to maximise the benefits of Australia’s strategic geography, alliances and key security partnerships.

Conclusion

Defence planning can no longer assume a 10-year warning time with which to prepare for major conventional conflict in Australia’s immediate area of strategic interest. This marks an important shift away from the strategic and capability judgements outlined in the 2012 Force Posture Review. The challenges of major power competition, coercion and military modernisation threaten to test the preparedness of the ADF to operate flexibly in a rapidly deteriorating strategic environment. The North West of Australia is on the frontline of great power competition and remains a potential target of coercion. There is crucial need therefore to reinforce its economic criticality to the Australian economy.

These challenges require a higher level connecting policy between the federal Government, the ADF and industry and a new force posture review that accepts the significance of the north-west to Australia’s security and sustainment. New developments in the AUKUS nuclear submarine pact and Gascoyne Gateway deep-water port proposal present the Australian Government with a timely window of opportunity to ensure the ADF is correctly geographically positioned to carry out its mandate in these uncertain times.

About the author

Marcus Schultz is a Research Assistant at the UWA Defence and Security Institute.

Notes

[1] Australian Government Department of Defence. 2020 Defence Strategic Update (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, 2020), 11-13, https://www.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/2020_Defence_Strategic_Update.pdf.

[2] The federal Labor Party has pledged it will initiate a new force posture review if elected in 2022. Commonwealth of Australia, Forty-Sixth Parliament First Session—Fifth Period (Canberra, ACT: House of Representatives, 2021), 9, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/chamber/hansardr/b82f60e7-9b0b-4339-8b31-3fa45ac099a7/toc

_pdf/House%20of%20Representatives_2021_09_01_9079.pdf.

[3] Allan Hawke and Ric Smith, Australian Defence Force Posture Review (Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, 2012), iii, https://www.defence.gov.au/Publications/Reviews/ADFPosture/Docs/Report.pdf.

[4] Australian Government Department of Defence. Defence White Paper 2013 (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, 2013), 24, https://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper/2013/docs/WP_2013_web.pdf.

[5] Hawke and Smith, Australian Defence Force Posture Review, i.

[6] Hawke and Smith, Australian Defence Force Posture Review, ii-iii.

[7] The Hon Scott Morrison MP, “Address – Launch of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update,” Prime Minister of Australia, 1 July, 2020, accessed August 14, 2021, https://www.pm.gov.au/media/address-launch-2020-defence-strategic-update.

[8] Australian Government Department of Defence. Defence White Paper 2013, 28; Australian Government Department of Defence. Defence White Paper 2016 (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, 2016), 71, https://www.defence.gov.au/

sites/default/files/2021-08/2016-Defence-White-Paper.pdf.

[9] Australian Government Department of Defence. 2020 Defence Strategic Update, 14.

[10] Australian Government Department of Defence. 2020 Defence Strategic Update, 29.

[11] “2021 Offshore Petroleum Exploration Acreage Release: Now Open,” Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, accessed October 14, 2021, https://www.industry.gov.au/news/2021-offshore-petroleum-exploration-acreage-release-now-open.

[12] “Mineral and Petroleum Industry Activity Review 2020-21,” Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, accessed October 14, 2021, http://dmp.wa.gov.au/About-Us-Careers/Latest-Resources-Investment-4083.aspx.

[13] Thomas Shugart, “Australia and the Growing Reach of China’s Military,” Lowy Institute, August 9, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/australia-and-growing-reach-china-s-military.

[14] “Western Australia’s Offshore Petroleum Industry,” Energy Information Australia, accessed October 14, 2021, https://energyinformationaustralia.com.au/wa-offshore-petroleum-industry.

[15] Jeffrey Wilson, Submission to WA Legislative Assembly Economics and Industry Standing Committee Inquiry into Challenges and Opportunities for the WA Economy (Perth, WA: Perth USAsia Centre, 2021), 1, https://perthusasia.edu.au/getattachment/4d3dd3c9-aeec-4a8a-bd33-5aea3fb47499/PUSAC-WAECON-Submission-August-2021.pdf.aspx?lang=en-AU.

[16] Australian Naval Institute and Naval Studies Group University of New South Wales (Canberra), Protecting Australian Maritime Trade (Port Adelaide, SA: Australian Naval Institute, 2020), 9, https://navalinstitute.com.au/wp-content/

uploads/Protecting-Australian-Maritime-Trade-Report-March-2020.pdf.

[17] Australian Naval Institute and Naval Studies Group University of New South Wales (Canberra), Protecting Australian Maritime Trade, 9.

[18] Vijay Sakhuja, “Indian Ocean and the Safety of Sea Lines of Communication,” Strategic Analysis 25, no. 5 (2001): 689, https://doi.org/10.1080/09700160108458989.

[19] Australian Naval Institute and Naval Studies Group University of New South Wales (Canberra), Protecting Australian Maritime Trade, 6.

[20] John Coyne, Tony McCormack and Hal Crichton-Standish, Running on Empty? A Case Study of Fuel Security for Civil and Military Air Operations at Darwin Airport (Barton, ACT: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2020), 29.

[21] Coyne, McCormack and Crichton-Standish, Running on Empty? A Case Study of Fuel Security for Civil and Military Air Operations at Darwin Airport, 14.

[22] Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, “Australia’s Fuel Security Package,” accessed November 11, 2021, https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-security/australias-fuel-security-package.

[23] “Liquid Fuels Stockholdings in Australia and the IEA Obligation,” Australian Institute of Petroleum, 1 September, 2017, https://www.aip.com.au/resources/liquid-fuels-stockholdings-australia-and-iea-obligation.

[24] Australian Naval Institute and Naval Studies Group University of New South Wales (Canberra), Protecting Australian Maritime Trade, 16.

[25] Peter Layton, “The Rise of Airpower in the Indian Ocean Region: How Australia Should Respond,” WA Defence Review, June 28, 2020, https://wadefencereview.com.au/a-changing-airpower-balance-in-the-indian-ocean-region-implications-for-australia.

[26] Captain Michael Beard, Protecting Australia’s Maritime Trade: The Need to Plan Now to Bring the Future into the Present (Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia 2021), 5, https://www.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Tac_Talks_

Issue%20_01_2021.pdf.

[27] “Contract awarded for Cocos/Keeling runway upgrades,” Australian Defence Magazine, February 4, 2020, https://www.australiandefence.com.au/defence/air/contract-awarded-for-cocos/keeling-runway-upgrades.

[28] Ewen Levick, “Cocos Runway to be Widened as Defence Looks North,” Australian Defence Magazine, April 18, 2019, https://www.australiandefence.com.au/defence/air/cocos-runway-to-be-widened-as-defence-looks-north.

[29] Levick, “Cocos Runway to be Widened as Defence Looks North,” Australian Defence Magazine.

[30] Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works: Air 555 Phase 1 Airborne Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance Electronic Warfare Capability Facilities Works (Canberra, ACT: House of Representatives, 2020), 4, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Hansard/Hansard_Display?bid=committees/commjnt/

64e0ae12-2166-4410-a5af-48b0624266d2/&sid=0001.

[31] Australian National Audit Office, 2019-20 Major Projects Report: MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (Canberra, ACT: Department of Defence, 2020), 271-72, https://www.anao.gov.au/sites/default/files/Auditor-General_Report_2020-2021_19_PDSS_MQ-4C_Triton_Remotely_Piloted_Aircraft_System.pdf.

[32] Levick, “Contract awarded for Cocos/Keeling runway upgrades.”

[33] “Joint Statement Australia-U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021,” Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, accessed October 8, 2021, https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/united-states-of-america/ausmin/joint-statement-australia-us-ministerial-consultations-ausmin-2021.

[34] “Joint Statement Australia-U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021,” Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.”

[35] Gascoyne Gateway, Pre-Budget Submission 2021-22 (Nedlands, WA: Gascoyne Gateway Ltd, 2021), 14, https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/171663_gascoyne_gateway_pty_ltd.docx.

[36] Gascoyne Gateway, Pre-Budget Submission 2021-22, 15, 23.

[37] Gascoyne Gateway, Pre-Budget Submission 2021-22, 15.

[38] “Single Jetty Deep Water Port and Renewable Hub,” Environmental Protection Agency, last modified July 5, 2021, https://www.epa.wa.gov.au/proposals/single-jetty-deep-water-port-renewable-hub.

[39] Melanie Hearse, “Australia’s First ‘Green’ Port Seeks to Serve Defence,” The Mandarin, accessed October 10, 2021, https://www.themandarin.com.au/169289-australias-first-green-port-seeks-to-serve-defence.

[40] Skye Rytenskild, “Captain Michael Edwards OAM: ‘Gascoyne Gateway Will Set a Benchmark in Sustainability’,” Informa Connect, September 8, 2021, https://www.informa.com.au/insight/gascoyne-gateway.

[41] Tom Corben, Ashley Townshend and Susannah Patton, “What is the AUKUS Partnership?” United States Studies Centre, September 16, 2021, https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/explainer-what-is-the-aukus-partnership.