Between a Rock and a Hard Place: A Risk Analysis of Australia’s Rare Earth Supply Chain Strategy and its Implications for National Security

23 June 2023 | Michael Hilliard

Executive summary

This policy brief examines the importance of Rare Earth Elements (REE) in next-generation electronics, renewable energy, and defence technologies, highlighting Australia’s reliance on international sources and the challenges posed by China’s current dominance in the global REE supply chain. The Australian government aims to position the country as a global leader in the critical minerals sector by collaborating with other nations, including the US, Japan, and Malaysia. To help achieve this goal, the government must allocate significant funding to expand programs like the National Reconstruction Fund, increase the availability of non-recourse loans, and foster collaborations between mining, chemical, and educational institutions. This paper proposes three recommendations to promote a secure and reliable REE supply chain, including expanding domestic refining and component creation capacity, increasing access to non-recourse loans to perspective extraction firms to promote private sector investment, and investing in the research and development of alternative production methods to increase sector efficiency. Overall though, the paper advocates the position that for Australia, collaboration with international partners will be essential to ensuring the longevity of domestic production in this sector.

Policy recommendations

- Federal and State governments should allocate significant funding to expand programs like the National Reconstruction Fund to help subsidise the production costs of refined REE products[1]. Such programs would help to subsidise the production costs associated with refining REE products and the creation of end-user components domestically, with the ultimate goal of artificially creating market competitiveness for Australian producers.

- The Federal Government should also increase the availability of non-recourse loans to private firms interested in investing in the REE sector[2]. This would encourage firms to increase capital investment into the sector without the fear of significant state interference in company management through state share purchases, or the potential impact of an insolvent REE operation on other sectors of their business.

- Federal and state governments must also look to foster collaborations between mining, chemical and educational institutions. Such collaborations would help to develop the necessary skills and knowledge to sustain the industry long-term, identify new research and development opportunities, and create a more resilient and secure supply chain for both the Australian and the US Departments of Defense[3].

Introduction

Rare earth elements (REE) are not only critical for the development of next-generation electronic components and renewable energy production and technologies, but also to the manufacturing and maintenance of cutting-edge defence systems, including fighter aircraft, guided missile systems, radar technologies, and advanced electronics. The demand for REE is expected to increase as defence technologies continue to advance, emphasising the strategic need for a secure and reliable national supply chain. Currently, Australia relies on international sources of REE, exposing the country to potential supply chain disruptions resulting from geopolitical conflicts, trade disputes, or export restrictions imposed by other nations.

In response to this predicament, the Australian government has begun implementing policies to support domestic REE production, including increasing funding for research and development, streamlining regulatory processes, and incentivising investment in the mining sector. These measures are necessary to ensure the security and resilience of Australia’s supply chain for defence-related materials and technologies, thereby safeguarding Australia’s national interests[4].

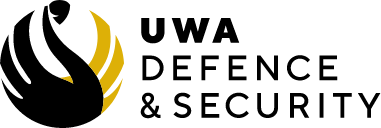

Figure 1: F-35 fighter rare earth elements. Source: Science and Technology Organisation of NATO

The Australian Government’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-2030[5] and Powering Australia discussion papers[6] outline the government’s plan for the development and management of critical minerals. The strategy aims to position Australia as a global leader in the critical minerals sector, with the papers identifying four key pillars: resource development, supply chain resilience, market diversification, and environmental, social, and governance considerations[7].

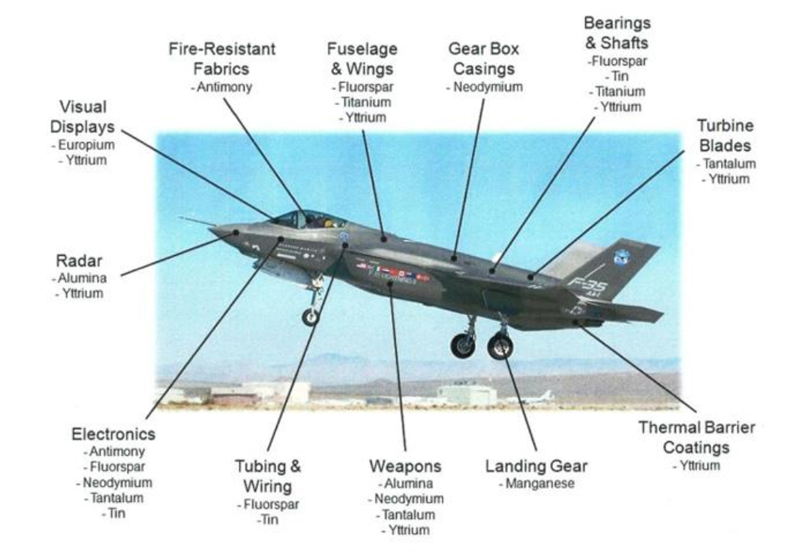

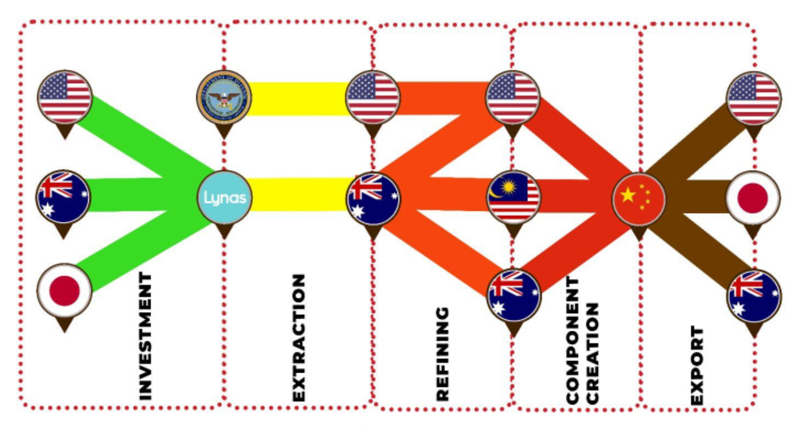

Australia has developed this comprehensive strategy to collaborate closely in the development of this sector with ally the United States (US) and close partners Japan and Malaysia, to secure friendly supply chains for critical minerals in the name of national security[8]. The US has expressed deep interest in developing these interconnected supply chains with Australia[9], with Lynas Rare Earths recently securing a $120 million contract with the US Department of Defense to establish a heavy rare earth separation facility in Texas[10]. The facility will process materials from the US Department of Defense stockpile and Lynas’ rare earth mine in Western Australia, increasing the US’s domestic production of rare earth elements. The establishment of a heavy rare earth separation facility is seen as crucial for both countries’ national security in the face of growing geopolitical tensions between Washington and Beijing, who currently dominate the majority of the REE market[11].

Australia’s reliance on international sources for REE exposes the country to potential supply chain disruptions and poses a significant challenge to national security. To address this, the Australian government should expand domestic refining and component creation capacity and increase access to capital, while collaborating with international partners to ensure the longevity and security of the REE supply chain.

Figure 2: Map of Lynas rare rarth supply chain. Source: Reuters[12]

Red: Exporting raw materials from Australia to Refineries in Malaysia and the US

Yellow: Exporting refined materials back to the US, Australia and Japan

Why this issue is so critical

With the demand for REE expected to increase as defence technologies continue to advance, Australian defence officials have emphasised the critical need for a secure and reliable supply chain for the future[13]. The production of just one of Australia’s main fighter aircraft, the F-35, requires a significant amount of REE to produce, approximately 420 kgs[14]. Therefore, any disruption to the REE supply chain could significantly affect Australia’s ability to maintain its defence capabilities and strategic advantage. The ongoing dominance of China in the global REE supply chain poses a significant challenge to the security and stability of other nations that rely on these resources.

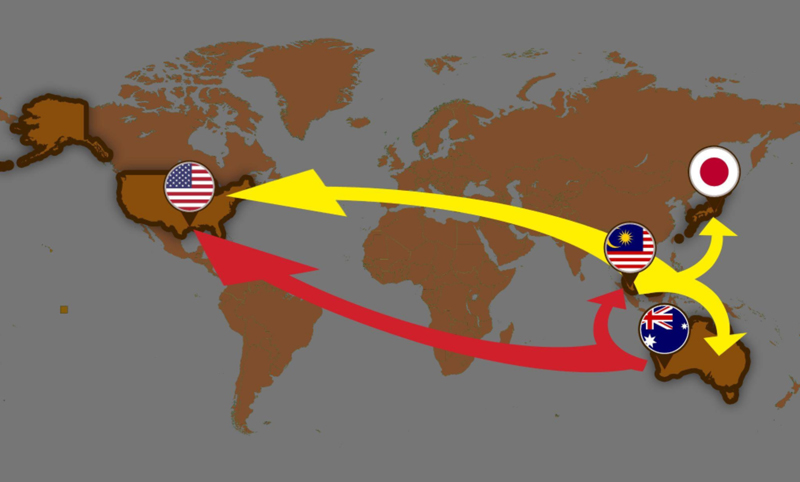

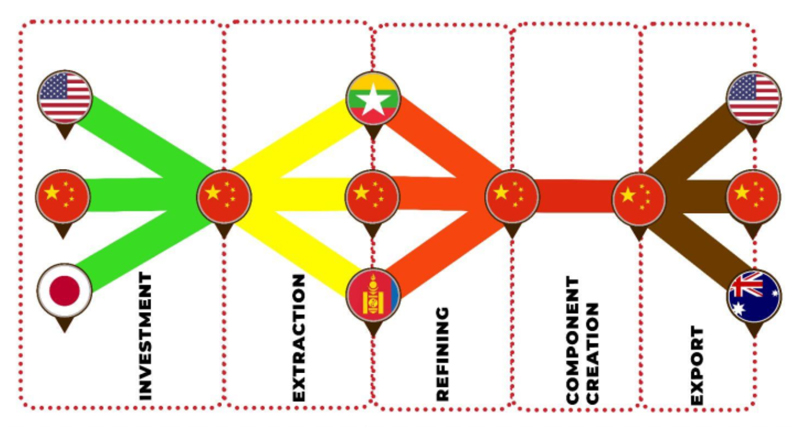

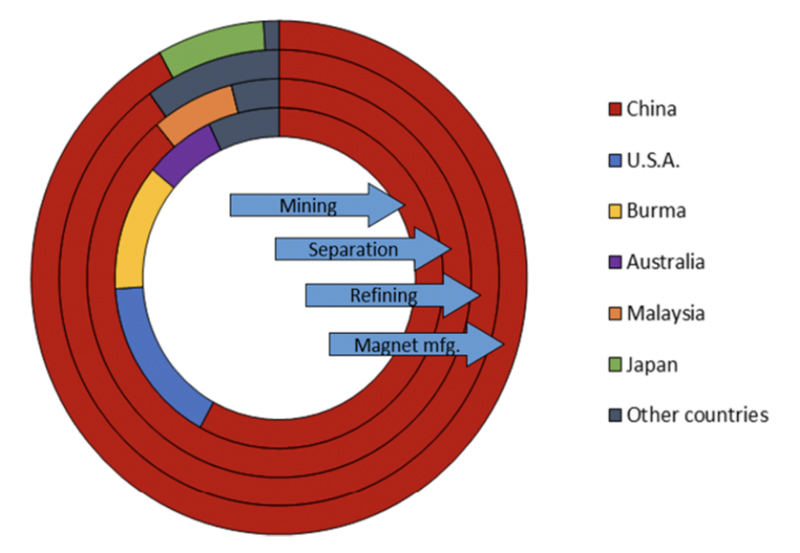

China’s substantial economic advantages over Australian REE producers, including preferential loans, affordable raw materials, subsidised labour, and less strict environmental regulations, have enabled Chinese companies to significantly out-compete Western miners in the global market[15]. Through this private market consolidation, Chinese firms at one point controlled over 85% of the global REE extraction market, posing a significant risk to the security and stability of other nations that rely on these resources for their national security[16].

Figure 3: World mine production of rare earth oxides. Source: US Geological Survey[17]

In a purely globalised free market, Australian enterprises would be unable to economically compete against these Chinese state-backed entities. This creates a situation where the Australian government is reliant upon uncompetitive private companies, vulnerable to bankruptcy and shutdown, for the production of key defence materials. To address this, the Australian government has implemented several policies to support domestic REE production, including increasing funding for research and development, streamlining regulatory processes, and incentivising investment in the mining sector, with the aim of safeguarding the country’s national interests[18].

Australia’s current policy

Publicly expressing apprehensions regarding the strategic risks present within their national REE procurement strategy, the Australian government has initiated the implementation of a targeted series of policies, aimed at rectifying the existing shortcomings in their current REE procurement schemes[19]. These measures manifest a steadfast commitment to mitigating the associated supply chain risks and ensuring uninterrupted access to REE resources, which as discussed earlier on, are of utmost significance for safeguarding national security and fostering domestic economic prosperity.

The principal blueprint for these policies is outlined in the Australian Government’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-30[20], along with the Powering Australia[21] discussion papers. These documents provide a comprehensive framework for the government’s intended approach to the development and management of critical minerals in the foreseeable future. With the overarching objective of positioning Australia as a global leader in the critical minerals sector, the strategy places notable emphasis on key minerals such as Lithium, Vanadium, Neodymium-Praseodymium, Scandium, and various other REE.

The discussion paper identifies four key pillars for the strategy:

- Resource development: The government aims to encourage investment in exploration, extraction, and processing of critical minerals within Australia. This includes streamlining regulations and approvals processes, promoting innovation, and supporting research and development.

- Supply chain resilience: Focuses on strengthening Australia’s critical minerals supply chain, from mining, to processing, to export. This includes improving infrastructure, promoting value-added processing, and fostering international partnerships.

- Market diversification: The government aims to diversify Australia’s critical minerals export markets beyond traditional trading partners. This includes identifying new markets, building relationships with emerging economies, and promoting trade and investment opportunities.

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations: The strategy emphasises the importance of responsible and sustainable critical minerals development. This includes promoting environmental best practices, ensuring community engagement and benefits, and addressing ESG risks.

The government policy also highlights the need for collaboration between government, industry, and stakeholders to achieve these stated objectives, with the overarching aim of bolstering private investor confidence toward the industry. The current roadmap sees the government looking to “Risk-Proof” the domestic producers, a crucial priority with many of the industries’ major producers like Lynas having come close to bankruptcy multiple times[22]. These investments by the federal government will endeavour to show investors that the state is willing to guarantee the longevity of domestic REE production, even against economic downturns or foreign market manipulation.

Australia’s endeavours with international partners

To secure REE supply chains and meet the growing demand both in Australia and abroad, the government has announced plans to further develop and secure interconnected supply chains with partner states. The strategy seeks to exploit the competitive economic advantages of each of these states for the expansion of REE production and refinement capabilities outside of China. The strategy prescribes working closely with other nations, such as the US, Japan, and Malaysia through a combination of both private and public investments, often funded in the name of national security[23].

The US in particular has expressed deep interest in developing interconnected REE supply chains with Australia through a process often referred to in the industry as “friendshoring”[24]. Recently, Australian mining company Lynas Rare Earths secured a $120 million contract with the US Department of Defense to establish a heavy rare earth separation facility in Texas[25]. The facility will process materials from the US Department of Defense stockpile and also Lynas’ rare earth mine in Western Australia, increasing overall US domestic production of REE. The contract is part of the US government’s plan to reduce its reliance on China for critical minerals[26]. Whilst the establishment of a heavy rare earth separation facility is seen by US defence officials as crucial for national security, just establishing these facilities may not be enough to provide the US with a long-term solution. The US has seen domestic REE mines like Mountain Pass in California go bankrupt[27] in the past by attempting to compete economically with cheaper-to-produce Chinese REE. Therefore, these new Lynas facilities being established within Texas are expected to require long-term state support to be able to compete economically in the global market against China[28]. The US intends to accomplish this by having much of the operational costs, and initial startup funding provided directly by the US government, with the intention of lowering Lynas’ overall production costs to a level somewhat economically comparable to China’s[29].

To the benefit of the US, Australia already has already developed off-shoring refinement capabilities for some years now, basing much of its Rare Earth refining capacity in partner countries to avoid the much stricter environmental regulations at home[30]. This is a particularly prominent issue impacting the REE sector as the refinement of REE often creates radioactive bi-products such as Thorium, increasing the cost of containment for producers when operating in countries with more stringent regulatory environments[31]. Lynas in particular has used Malaysia as home to its larger refining facilities, with Lynas announcing plans to increase its refining capabilities after securing an extension of its Malaysian operating licence. Seeing the potential here, the Japanese government has also strengthened its commitment to invest in Australia’s rare earth sector by signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Australian government. The MoU seeks to boost investment in Australia’s rare earth mining, processing and recycling industries. The move comes as Japan also seeks to diversify its supply chain of REE and reduce its dependence on China amid growing regional tensions[32].

Rather than these nations attempting to develop individual REE sectors, they are instead working to build an interconnected and efficient REE supply chain. This fracturing of the process won’t provide any one nation with full sovereignty over supply, but it will provide an avenue to reduce reliance on China and boost interconnections between regional partners and allies.

Problems with the current strategy

The global REE industry faces significant challenges due to near monopolistic control by China, which has developed a complete value chain from mining to manufacturing for the production of advanced REE end-products[33]. While extraction and primary beneficiation of REEs are relatively easy, refining them to metals and alloys is a customer-tailored process that requires a complete value chain to supply end customers in Western markets. China is currently the only country that has developed this complete value chain at scale, comprising numerous independent companies dedicated to rare earth research and production, each providing highly differentiated technologies, processing, formulation, or component-specific applications[34].

Figure 4: Lynas rare earth production chain. Source: Reuters[35]

Figure 5: Chinese state REE production chain. Source: Resources Policy[36]

China’s production capacity and vertically integrated supply chain cannot be easily duplicated in the short term, and will take several years of concerted effort for Australia and the rest of the world to catch up[37]. Even though mining production outside of China has increased significantly during the last few years, China’s monopoly remains intact outside of a few key niches. Customers often prefer sourcing their REE inputs from China over standalone Western mining firms who are unable to recreate this same comprehensive REE value chain. For many private consumers, Australia still appears to lack the sought-after scaleable downstream processing[38].

Figure 6: Supply chain stages for sintered NdFeB magnets. Source: US Department of Energy

From center: Rare earth mining, oxide separation, metal refining and magnet manufacturing.

For firms looking to purchase REE at a larger scale from sources outside of China, REE processing capacity remains low, and the processing costs stay high. These disparities between national REE producers also widen further as Chinese producers enjoy the benefits of state support in input sourcing and preferential loans from the central government. Meanwhile, Western producers are forced to work within a purely market system, and therefore have a greater risk of bankruptcy in the event of financial trouble. In the long run, it is also almost certain that Chinese production costs will remain lower than those of companies like Lynas due to factors such as low labour costs, and lower environmental regulatory standards[39]. Western companies can only maintain international market competitiveness with the help of significant government investment, backing and support, and whilst the Albanese and Biden administrations have committed to these measures, it can’t be guaranteed that subsequent administrations won’t seek to reverse these actions. At present, the REE refining industry will likely continue to face difficulty attracting the required large-scale private research and investment whilst capital investors have concerns that the industry could be made unfeasible overnight by a simple change in legislation[40].

Recommendations

The issue around REE procurement poses several complex challenges that will require extended government intervention in order to maintain long-term security and confidence. Although several recommendations could be proposed, three salient ones are identified below.

Firstly, to mitigate the evident bottlenecks in Australia’s current supply chains, the country should rapidly expand its refining and component creation capacity. However, given that Chinese production costs are below Australia’s breakeven point, the Australian government will need to provide financial assistance to adequately subsidise production costs in order to achieve market competitiveness.

This current economic reality within the sector underscores the precarious financial status of even Australia’s largest REE producer, Lynas, which has found itself on the brink of bankruptcy on multiple occasions. The REE industry’s thin profit margins, high costs, amid market manipulation from China, reinforce the need for the Australian government to provide a fiscal safety net for companies seeking to expand their operations in this sector. This safety net should sufficiently reassure private investors to encourage capital investment[41]. The government could seek to achieve this bolstering of consumer confidence by purchasing a 49% stake in some of Australia’s larger REE producers through vehicles like the Future Fund[42], or Clean Energy Finance Corporation[43], thereby providing the much-needed capital infusion. However, this approach carries risks, as private investors may feel hesitant to invest in an enterprise with such heavy state involvement[44]. A preferable approach would be to provide the desired investment capital through programs such as the National Reconstruction Fund[45]. Such investments would subsidise some of the production costs associated with REE refining and incentivise firms to expand their REE refining capacity even when the market does not[46].

Second, in the interest of promoting private sector investment within the industry, the government should seek to expand its allocations of Non-Recourse loans to the sector. Non-recourse loans represent a form of financial arrangement whereby the lender’s sole recourse lies in the collateral furnished by the borrower, without imposing personal liability on the latter[47]. In the specific context of Australia’s strategic REE mining sector, a prospective REE mining company could use these loans to establish a new minesite with the knowledge that the lender can only seek recovery from the collateral used to secure the loan (often the new mine site itself) if the investment becomes a financial liability to the mining firm. The utilisation of these non-recourse loans assumes significance as a mechanism to “risk-proof”[48] the industry. By extending financial support to mining enterprises while minimising exposure to excessive risk, these loans facilitate the provision of funding for critical activities such as exploration, development, and production, thereby attenuating the financial uncertainties inherent in prospective rare earth mining ventures and promoting the sector’s stability and long-term viability[49].

If the unlikely worst-case scenario were to occur and the domestic industry does collapse, these REE refineries would simply transition into state management, with no scopious losses incurred by private investors[50]. The state could then maintain the facilities until the market stabilises and then refloat the asset back onto the market without incurring detrimental interruptions to its domestic production[51]. In the past, the risk of significant financial loss in this sector has deterred many potential investors, therefore Non-Recourse loans have the potential to mitigate investor risk and instil much-needed investor confidence into the sector[52]. An expansion of market access to lease loans, particularly during a period of increased borrowing costs, presents an opportunity for the government to spur private sector involvement in the sector[53], promoting the development of a more robust and resilient domestic REE industry[54].

Finally, in addition to the expansion of these loans and grants, it is also imperative that a concerted effort be made towards research and development of alternative production methods. This includes the development of new technologies[55] for extracting and refining REE, in an effort to develop more sustainable and streamlined processes, precipitating better yields of REE from future supplies. Moreover, further efforts should also be made to ramp up domestic REE recycling capabilities[56]. Investment in the research and development of REE recycling capabilities, reliance on virgin REE sources can be reduced, leading to a more sustainable and circular supply chain, while also minimising environmental impacts[57].

Australian universities are likely to be at the forefront of these efforts and have an established reputation as world leaders in geological and chemical innovation. The Australian government should seek to capitalise on this existing expertise by allocating additional grants, programs, and funding to institutions conducting research in the field of REE. By doing so, the government can ensure that the country remains at the forefront of REE innovation, leading to the development of new technologies that will help secure the nation’s REE supply chain, and ultimately contribute to the growth and development of the domestic REE industry[58].

Conclusion

The demand for REE is expected to increase as defence technologies advance, making it crucial for Australia to develop a secure and reliable supply chain. At the present time, Australia currently relies heavily on international sources of REE, exposing the country to potential supply chain disruptions from geopolitical conflicts, trade disputes, or export restrictions imposed by other nations, and China’s dominance in the global REE supply chain poses a significant challenge to the security and stability of any nation that relies on a single state for these critical resources. The Australian government has implemented several policies to support domestic REE production, including increasing funding for research and development, streamlining regulatory processes, and incentivising investment into the mining sector, with the aim of positioning Australia as a global leader in critical minerals. Overall though, collaboration with partners such as the US, Japan, and Malaysia will be essential to securing Australia’s supply chains for critical minerals, and strategically crucial to securing the longevity of domestic production capacity in this sector going forward.

About the author

About the author

Michael Hilliard is a Research Analyst Intern in the Semester 1 2023 UWA DSI Internship Program. He is also a consultant working as an advisor and defence policy writer for the UK, US and Australian governments with a focus on Eurasian defence policy.

Notes

[1] Australian Government. (2020). Supporting Australia’s critical minerals industry. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/supporting-australias-critical-minerals-industry

[2] Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. (2020). Australia’s critical minerals strategy 2019. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/australias-critical-minerals-strategy-2019

[3] United States Department of Defense. (2019). Executive summary of the report to congress on the US strategic and critical minerals policy. Retrieved from https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/Downloads/Reports/Strategic-and-Critical-Minerals-Report-to-Congress-Executive-Summary.pdf

[4] Gholz, Eugene. Rare earth elements and national security. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2014.

[5] Australian Government. (2023). Critical minerals strategy 2023-2030. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030

[6] Australian Government. (2022). Powering Australia discussion paper. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/powering-australia-discussion-paper

[7] Chaumette, D (2021), Risks of disruptionof supply chains for military and aerospace industries, NATO Science and Technology Organization Collaboratio Support Office.

[8] O’Rourke, D., & Hannan, E. (2022, March 1). Australia seeks critical minerals link with US, Japan and South Korea. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/c0c37197-e74a-42e9-9e31-92bfe0b5e5b5

[9] Flannery, T. (2021, December 14). Lynas secures US Department of Defense rare earths supply contract. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/timtreadgold/2021/12/14/lynas-secures-us-department-of-defense-rare-earths-supply-contract/?sh=40faa5a5621f

[10] Bryant, L. (2021, December 15). Lynas secures $120m US Department of Defense contract for Texas heavy rare earths separation facility. The West Australian. Retrieved from https://thewest.com.au/business/mining/lynas-secures-120m-us-department-of-defence-contract-for-texas-heavy-rare-earths-separation-facility-ng-b88621544z

[11] S&P Global. (2021, November 15). Lynas steps up to tackle global rare earths supply chain challenges. S&P Global. Retrieved from https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/lynas-steps-up-to-tackle-global-rare-earths-supply-chain-challenges-67084771

[12] Menon, Praveen. “Australia’s Lynas gets $120 mln Pentagon contract for U.S. rare earths project.” Reuters, (2022, June 15). https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/australias-lynas-secures-120-mln-pentagon-contract-us-rare-earths-facility-2022-06-14

[13] Australian Government Department of Defence. (2022). Critical minerals. https://www1.defence.gov.au/industry/critical-minerals

[14] Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. (2022). Rare earths. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/rare-earths

[15] Morrison, Wayne M., and Rachel Tang. “China’s rare earth industry and export regime: economic and trade implications for the United States.” (2012).

[16] Council on Foreign Relations. (2021). Rare earth metals and national security. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/rare-earth-metals-and-national-security

[17] US Geological Survey (2017), Global Rare Earth Oxide (REO) production. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/rare_earths/ree-trends-2010.pdf

[18] Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. (2022). Rare earths. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/rare-earths

[19] Australian Government. (2023). Critical minerals strategy 2023-2030. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030

[20] Australian Government. (2023). Critical minerals strategy 2023-2030. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030

[21] Australian Government. (2022). Powering Australia discussion paper. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/powering-australia-discussion-paper

[22] Ayres, Robert U. “The business case for conserving rare metals.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 143 (2019): 307-315.

[23] Australian Government. (2023). Critical minerals strategy 2023-2030. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030

[24] Vivoda, Vlado. “Friend-shoring and critical minerals: Exploring the role of the Minerals Security Partnership.” Energy Research & Social Science 100 (2023): 103085.

[25] Menon, Praveen. “Australia’s Lynas gets $120 mln Pentagon contract for U.S. rare earths project.” Reuters, (2022, June 15). https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/australias-lynas-secures-120-mln-pentagon-contract-us-rare-earths-facility-2022-06-14

[26] Hammond, David R., and Thomas F. Brady. “Critical minerals for green energy transition: A United States perspective.” International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment 36, no. 9 (2022): 624-641.

[27] Karayannopoulos, Constantine, and Vasileios Tsianos. “Lessons from Three Decades in the Rare Earth Trenches.” In Critical Minerals, the Climate Crisis and the Tech Imperium, pp. 81-106. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023.

[28] Smith, Braeton J., Matthew E. Riddle, Matthew R. Earlam, Chukwunwike Iloeje, and David Diamond. Rare Earth Permanent Magnets-Supply Chain Deep Dive Assessment. USDOE Office of Policy (PO), 2022.

[29] ABC News. (2021, March 8). US signs deal with Australian rare earths producer to bolster industry and reduce reliance on China. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-09/us-lynas-deal-rare-earths-australia-industry-china/13230468

[30] Wu, Haitao, Yu Hao, and Siyu Ren. “How do environmental regulation and environmental decentralization affect green total factor energy efficiency: Evidence from China.” Energy Economics 91 (2020): 104880.

[31] Gielen, Dolf, and Martina Lyons. “Critical materials for the energy transition: Rare earth elements.” International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, UAE 48 (2022).

[32] Australian Trade and Investment Commission. (2021, March 31). Japan and Australia sign deal to boost rare earth production.

[33] Binnemans, K., Jones, P. T., Blanpain, B., Van Gerven, T., Yang, Y., Walton, A., & Gutiérrez-Sánchez, C. (2013). Recycling of rare earths: a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 51, 1-22.

[34] Li, Y., Chen, G., Wang, L., & Li, D. (2015). China’s rare earth industry and its role in the international market. Resources Policy, 46, 1-12.

[35] Menon, Praveen. “Australia’s Lynas gets $120 mln Pentagon contract for U.S. rare earths project.” Reuters, (2022, June 15). https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/australias-lynas-secures-120-mln-pentagon-contract-us-rare-earths-facility-2022-06-14

[36] Zhang, J., Zhao, X., Tang, X., & Zhang, W. (2020). A comparative study on the evolution of rare earth policies in China, Japan, and the US. Resources Policy, 65, 101550.

[37] Zhang, J., Zhao, X., Tang, X., & Zhang, W. (2020). A comparative study on the evolution of rare earth policies in China, Japan, and the US. Resources Policy, 65, 101550.

[38] Binnemans, K., Jones, P. T., Blanpain, B., Van Gerven, T., Yang, Y., Walton, A., … & Gutiérrez-Sánchez, C. (2013). Recycling of rare earths: a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 51, 1-22.

[39] Coelli, Michael, James Maccarrone, and Jeff Borland. “The dragon down under: The regional labour market impact of growth in Chinese imports to Australia.” Regional Studies (2023): 1-16.

[40] Hatch, C. (2021). Can Western rare earth miners compete with China? Mining Technology. Retrieved from https://www.mining-technology.com/features/can-western-rare-earth-miners-compete-with-china

[41] Xiang, Dong, and Andrew C. Worthington. “The impact of government financial assistance on the performance and financing of Australian SMEs.” Accounting research journal (2017).

[42] Future Fund (2023). “How we invest” FutureFund (2023 May 10), https://www.futurefund.gov.au/investment/how-we-invest

[43] Clean Energy Finance Corporation (2023). Where We Invest: Resources, CEFC, (2023 May 10), https://www.cefc.com.au/where-we-invest/sustainable-economy/resources

[44] Demirel, Hatice Cigdem, Wim Leendertse, and Leentje Volker. “Mechanisms for protecting returns on private investments in public infrastructure projects.” International Journal of Project Management 40, no. 3 (2022): 155-166.

[45] National Reconstruction Fund (2022), “National Reconstruction Fund: diversifying and transforming Australia’s industry and economy”. Department of Industry, Sciences and Resources, (2022 October 27). https://www.industry.gov.au/news/national-reconstruction-fund-diversifying-and-transforming-australias-industry-and-economy

[46] Australian Critical Minerals Prospectus (2020). Critical Minerals: Securing our Future. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021

[47] Arif, M., Nazir, M. S., Qamar, M. A. J., & Abid, A. (2022). Project finance and recourse loans: determining debt choices in political, economic and financial risk positions under global perspective. European Journal of International Management, 18(2-3), 379-402.

[48] Aghabekyan, Anna. “Investment protection in non-recourse project finance: the lender’s perspective.” PhD diss., American University of Armenia, 2019.

[49] Geroe, Steven. “Non-recourse project financing for concentrated solar thermal power.” Utilities policy 60 (2019): 100937.

[50] Perchard, Andrew, and Keith Gildart. “Managerial ideology and identity in the nationalised British coal industry, 1947–1994.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 44, no. 1 (2023): 230-261.

[51] Newbery, David M., and Michael G. Pollitt. “The restructuring and privatisation of Britain’s CEGB—was it worth it?.” The journal of industrial economics 45, no. 3 (1997): 269-303.

[52] Rautalahti, Eero, and Edwards Wildman. “Non-recourse Financing for Mines.” In The principles of project finance, pp. 245-256. Routledge, 2016.

[53] Aghabekyan, Anna. “Investment protection in non-recourse project finance: the lender’s perspective.” PhD diss., American University of Armenia, 2019.

[54] Srinivasagan, T. “Privatization of rare earth mining: Today’s need for India”. Beach Minerals Prodcuers Association (2017 Mar 2), https://beachmineral.com/privatization-rare-earth-mining-todays-need-india

[55] Kenzhaliyev, B. K. (2019). Innovative technologies providing enhancement of non-ferrous, precious, rare and rare earth metals extraction. Kompleksnoe Ispolʹzovanie Mineralʹnogo syrʹâ, 310(3), 64-75.

[56] Lukowiak, Anna, Lidia Zur, Robert Tomala, Thi Ngoc LamTran, Adel Bouajaj, Wieslaw Strek, Giancarlo C. Righini, Mathias Wickleder, and Maurizio Ferrari. “Rare earth elements and urban mines: Critical strategies for sustainable development.” Ceramics International 46, no. 16 (2020): 26247-26250.

[57] Ali, Saleem H. “Social and environmental impact of the rare earth industries.” Resources 3, no. 1 (2014): 123-134.

[58] Massari, Stefania, and Marcello Ruberti. “Rare earth elements as critical raw materials: Focus on international markets and future strategies.” Resources Policy 38, no. 1 (2013): 36-43.